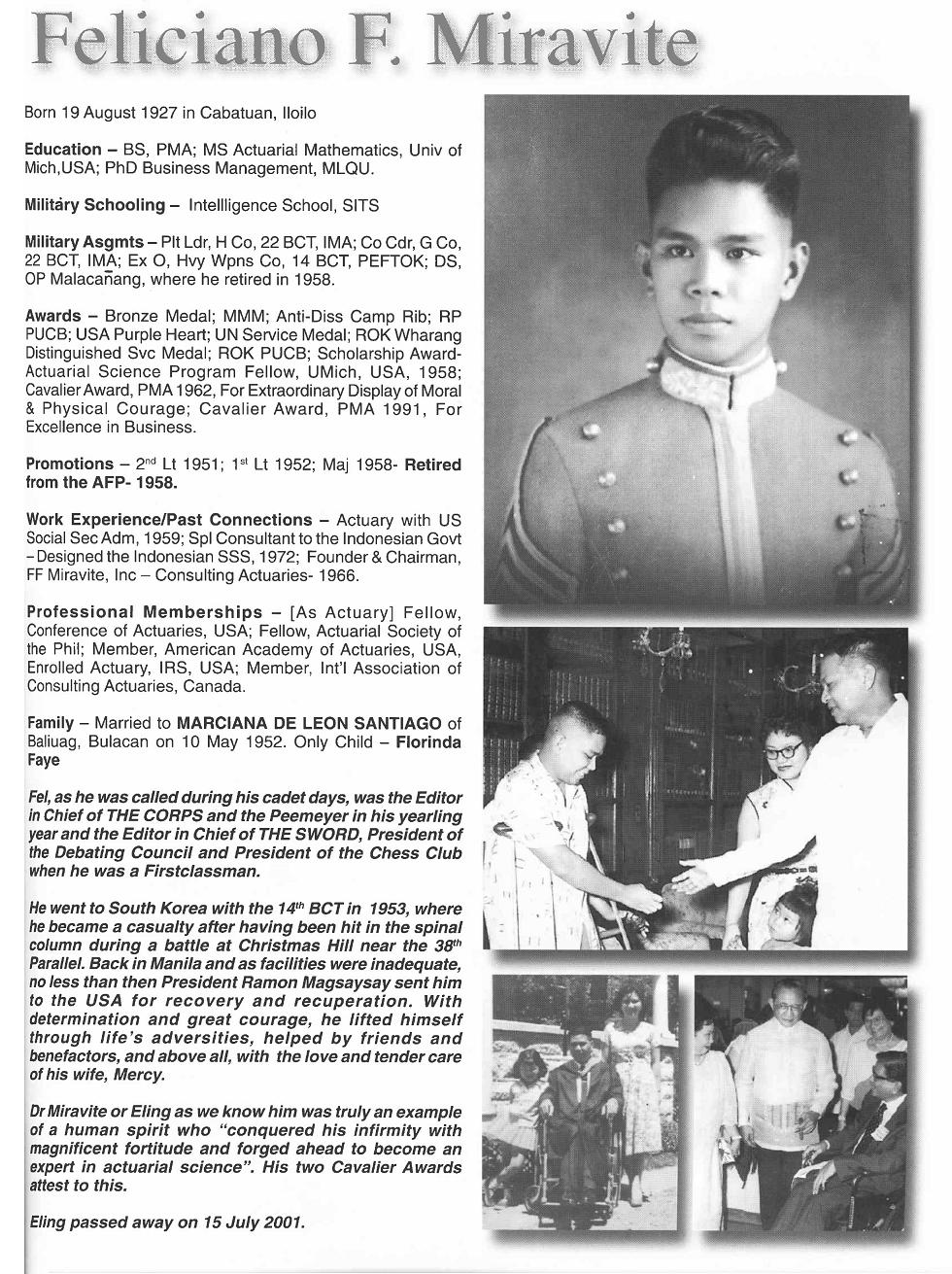

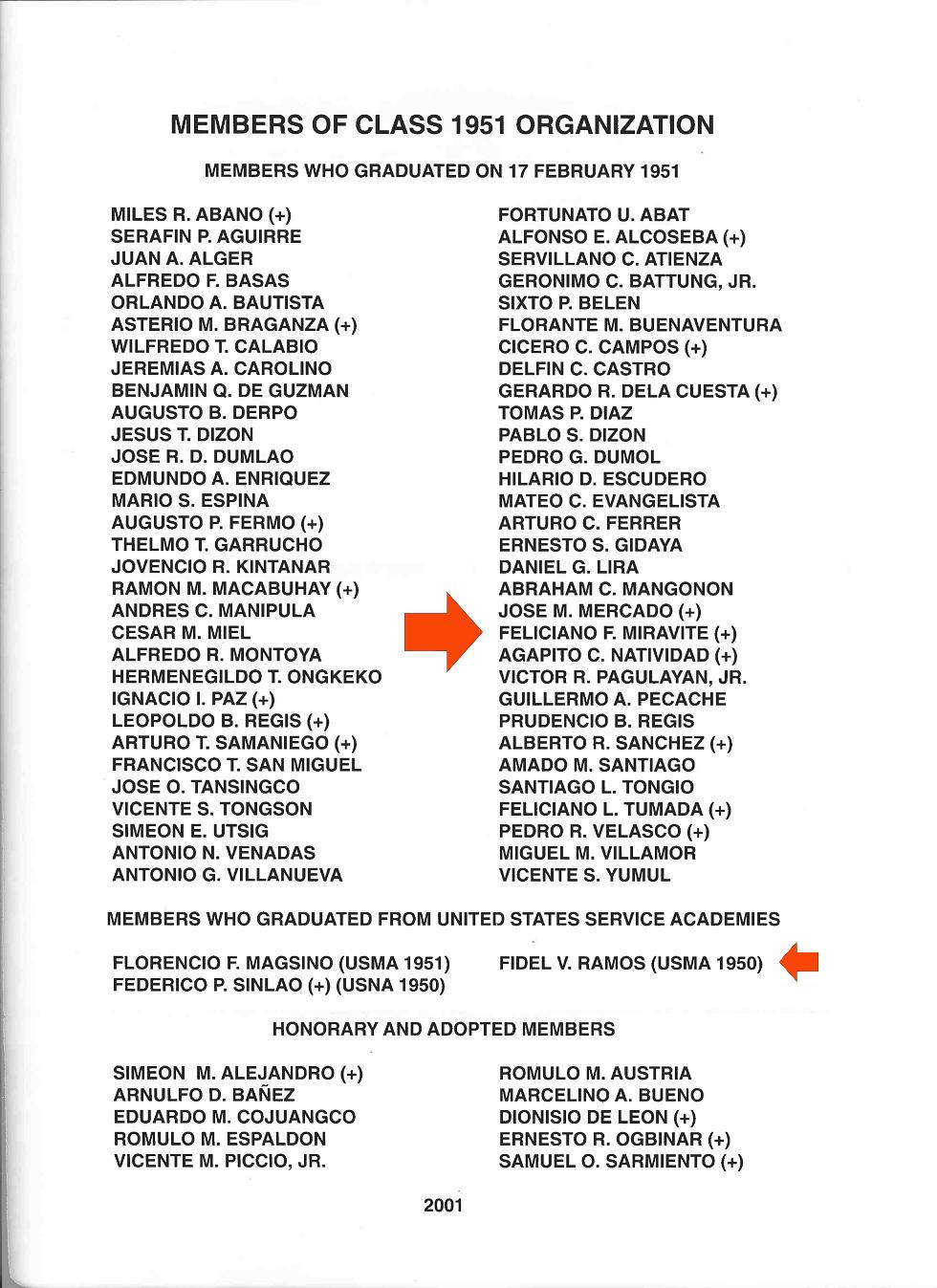

At the Philippine Military Academy

as a Plebe

|

with wife Mercy de Leon Santiago

on May 10, 1952

|

with President Ramon Magsaysay in 1953

|

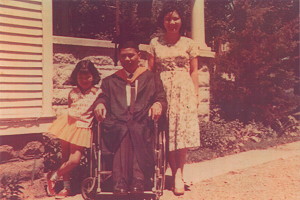

Graduating from University of Michigan with

a Master's Degree in Actuarial Mathematics

|

with classmate President Fidel V. Ramos

of PMA Class 1951

|

with wife Mercy, after 49 years

|

|

"A PLACE IN THE SUN

by Feliciano Fajardo Miravite, Consulting Actuary

As a 2nd Lieutenant in the Philippine Army in 1952

|

More than twenty-one years ago, on one lonely hill above the 38th parallel in the northern portion of the Korean peninsula, exactly a few minutes after midnight on July 15, 1953, volleys after volleys of enemy mortar shells fell on our line.

A few days earlier, the Philippine Battalion, which was attached to the U.S. 45th Division, moved from its sheltered position at Satae Ri Valley into an exposed flank of the United Nation's line to fill the gap caused by the annihilation of the Fifth Division of the South Korean Army.

It was at this moment that a fragment of those volleys of 82 millimeter mortar shells entered my body and lodged at my spinal column. The impact was sudden. My first impression was: I had lost my legs. It was only after one of the "medics" informed me that my legs were intact, that I knew then I had lost the use of both of them.

• • •

The sun was shining on my face as I waited on a stretcher in front of the U.S. Army Surgical Hospital (six miles behind the frontline) for my turn in surgery. A few hours back, I had just been through a nightmare. As I was being carried down the hill after getting hit, mortar shells were exploding everywhere. When at last I got to the ambulance, the ambulance could not get out of the mudhole (while the shells continued exploding). The ambulance inched itself out of the mud and dirt and the explosions in the pitch of darkness. I could hear the explosions faintly as we finally moved farther to the rear of the line.

I could feel the heat of the sun getting more intense as I was being wheeled into the operating room. I knew then that it was going to be a new life for me.

It was and it still is.

• • •

It was indeed the beginning of a great battle. This battle was to be waged inside me, in the hospitals, and in my mind. The Korean war ended 12 days after I got injured, but I continued with my own private war. The stakes were high. I had a wife who was in the family way and at that time I was only 26 years old. A long bleak future was ahead of me indeed. This kind of battle was bigger than that fought in the battlefield.

In the early days of my injury, as I stretched on my back completely helpless, I did not have the time to complain about the rather strict medical attention given to me, probably because I had been so helpless anyway. I therefore gave myself completely to the medical program of the hospital. Furthermore, even if I did complain about the stringent hospital procedures, I doubted if I could have been heard. The whole program to rehabilitate me, therefore, was left with the professionals and to their complete mastery of the techniques. It would have been different had I had some hand in my own rehabilitation, because as a patient, I would have selected the most convenient and the easiest path which is the road of least resistance. This could have been a great disaster.

As a result of the excellent care, I was lucky to prevent the occurence of complications that comes with the spinal cord injury itself. This situation could be achieved in a rather swift manner but the road to rehabilitation was a long process.

After several months of feeling sorry for myself, I awakened to the reality that there was no time to further linger on with this type of sadness. The thought of regaining the use of my limbs had always been there; it was allright had it come back, but the question with this trend of thinking was that no provision was made for the eventuality that it will not return. I was already blaming the whole world for my situation, and slowly I was changing my attitude into one who was a cynic, morose and negative thinker.

But the idea of doing nothing for the rest of my life disturbed me deeply. Although I was to be confined in a wheelchair for the rest of my life, this thought did not bother me much. It was the thought that I could not be of use or I could not accomplish anything that really bothered.

A few paragraphs back, I mentioned that I fought a bigger battle in my mind than in the battlefield. Somehow, the mind developed some kind of lethargy associated with disability. They seemed to me inseparable; and, therefore difficult to dissociate one from the other.

As soon as the mental attitude was changed, and the block removed, the planning of future steps was simple. A new vista was opened. A new profession or vocation had to be started, several factors had to be studied. I was not ambitious in my quest for the answer to deep-seated questions. It was not even in my mind to return to gainful employment. I was only aiming at proving one point: whether I could still accomplish anything.

This I set to prove by returning to school.

At the time I was preparing to study at Michigan, I had no idea what structural barriers I would encounter. I looked at the pictures of the buildings and it was discouraging to note that the building where the Department of Mathematics was holding its classes had more than 20 steps in front, something which would be impossible to negotiate even once a day for four semesters. In addition to this, the problem of how to move through the snow was overwhelming. I never had any inkling on how I would fare in the snow. This ignorance probably saved me from reversing my decision to study.

These problems seemed to be impossible to solve, especially at a distance, but as I was face-to-face with them, they seemed to have automatically disappeared. There was no need for me to negotiate a flight of 20 steps, as there was an elevator at the rear. In buildings where I could not get in, my professors were kind enough to change the rooms to a building accessible to me. As to the snow, all the students were kind enough to give my chair a push out of snow, mud or enbankment.

Today, the University of Michigan, as most schools in the U.S., is provided with ramps and accesses to enable the disabled to move about. Ann Arbor, where the University of Michigan is located, as well as other cities and towns, has transportation systems for the disabled. Twenty years ago, these were too good to be true.

Towards the end of my master's program, a number of insurance companies came to the campus to interview the graduating class. We were about 14 in the class against 50 or so companies. The prospect of getting a job was very favorable and how I needed it. And yet as I went through the ordeal of being interviewed, I never showed any sign that I needed one badly. This feeling was a basic feeling of a human being, I thought, irrespective of disabilty and non-disability. While my family in Ann Arbor was living on a complete restricted budget, I had to preface every interview that if I should get employed, it should never be out of pity because I would never accept a special employment condition.

I finally found myself one week after graduation employed as an actuary of the U.S. Social Security Administration in Washington, D.C. I found the working condition perfect and since it was a federal job, it offered plenty of room for opportunities. I must admit this started it all until I got an offer to join another company here at home.

At this point, I could not believe the fact that I was employed. My dogged determination to take graduate schooling was only to prove a point that despite a depressing disability, I could completely finish a course to my liking. But surely, it never occured to me that I should return to gainful employment.

And so, it was some sort of a personal victory when I started working for the U.S. Social Security Administration in Washington, D.C., exactly on June 22, 1959, 9 days after completing my M.S. in Michigan. This was almost six years since the world blacked out in one early morning volley of enemy fire in North Korea.

It was a very satisfying feeling and this simple tactical victory I used as an argument whenever I embarked later in other serious undertakings in life fraught with risks.

• • •

My own struggle for a "place in the sun" is tiny compared to many others in the past. At this point, it might be fitting to mention that the person who set up the most coveted prize in many fields of endeavor was Nobel - who himself suffered some sort of disability. This interesting sidelight might not be known to the vast majority of us. But, it may seem appropriate to mention that such a coveted prize was made thru the grit, labor and talent of one disabled person. We might call this as well as the gift of the disabled to humanity.

History is replete with illustrious people, who despite their most depressing physical condition, rose above to heights unprecedented. We might mention Beethoven, who despite his deafness produced the most beautiful music of all times during his period of disability; Franklin D. Roosevelt, who guided his country and the allies to win the Second World War, and many others. It was not their disability that won for them the plaudits of humanity, it was their ability.

But we must not forget those who have helped in their most trying times. The army of relatives, friends, benefactors, professors, nurses, therapists, doctors and other scientists who were fighting a great battle indeed to alleviate the condition of the disabled. In addition to those mentioned, I would like to mention my own particular case, the unflinching support of my wife who has stood by me during all these years.

I would like to conclude this short talk by addressing the disabled himself. As one who may be considered as completely rehabilitated and who now look into the future with more confidence, I would not want to forget the daily struggle of those who, like me, are caught in the moment of indecision. My advice would be to accept the disability and move forward.

To the army of private citizens, nurses, therapists, doctors, scientists and other professionals who have spent time, money and effort to alleviate a lot of those who have been unable to care for themselves, yours is an unselfish devotion to the cause of humanity. I do hope you could continue to support the struggle of the disabled for a "place in the sun".

To those who are in the government holding positions which can influence government decisions - to take the initiative in providing the correct atmosphere in the advancement of the disabled. We might mention a few steps like the setting up of architectural regulations to eliminate structural barriers - by constructing ramps in the streets, providing accesses to public and private buildings alike for the disabled. Another worthy steps would be to request corporations in the private sector especially those receiving government subsidies and enjoying tax exemptions to employ and accommodate the disabled in their working force. For in the employment of the disabled, the government is placing him at a level that can make him contribute to the economy of the nation, by giving him an opportunity to pay taxes to the government, instead of having him stay on government dole-outs. A big portion of the disabled population can work given the opportunity. The private sector will be more than happy to accommodate such a move by the government, since hiring the handicap, as the experience shows in the U.S. and Europe, has improved businesses. It may be appropriate to suggest, at this point, to create an office which we may call "The Presidential Committee for the Employment of the Physically Handicap".

There is truism in the saying that the strength of the nation lies in the strength of its people. Consequently, the government is as weak as the people. For in the final analysis, a nation cannot go forward, leaving a segment of the disabled behind.

This situation can aptly be described in the words of John Donne's in his "The Tolling Bell - A Devotion". It says: "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promentory were, as well as if a manor of thy friends or if thine own; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee".

I thank you.

A Place in the Sun was a speech given by Dr. Feliciano F. Miravite sometime in the 1970's.

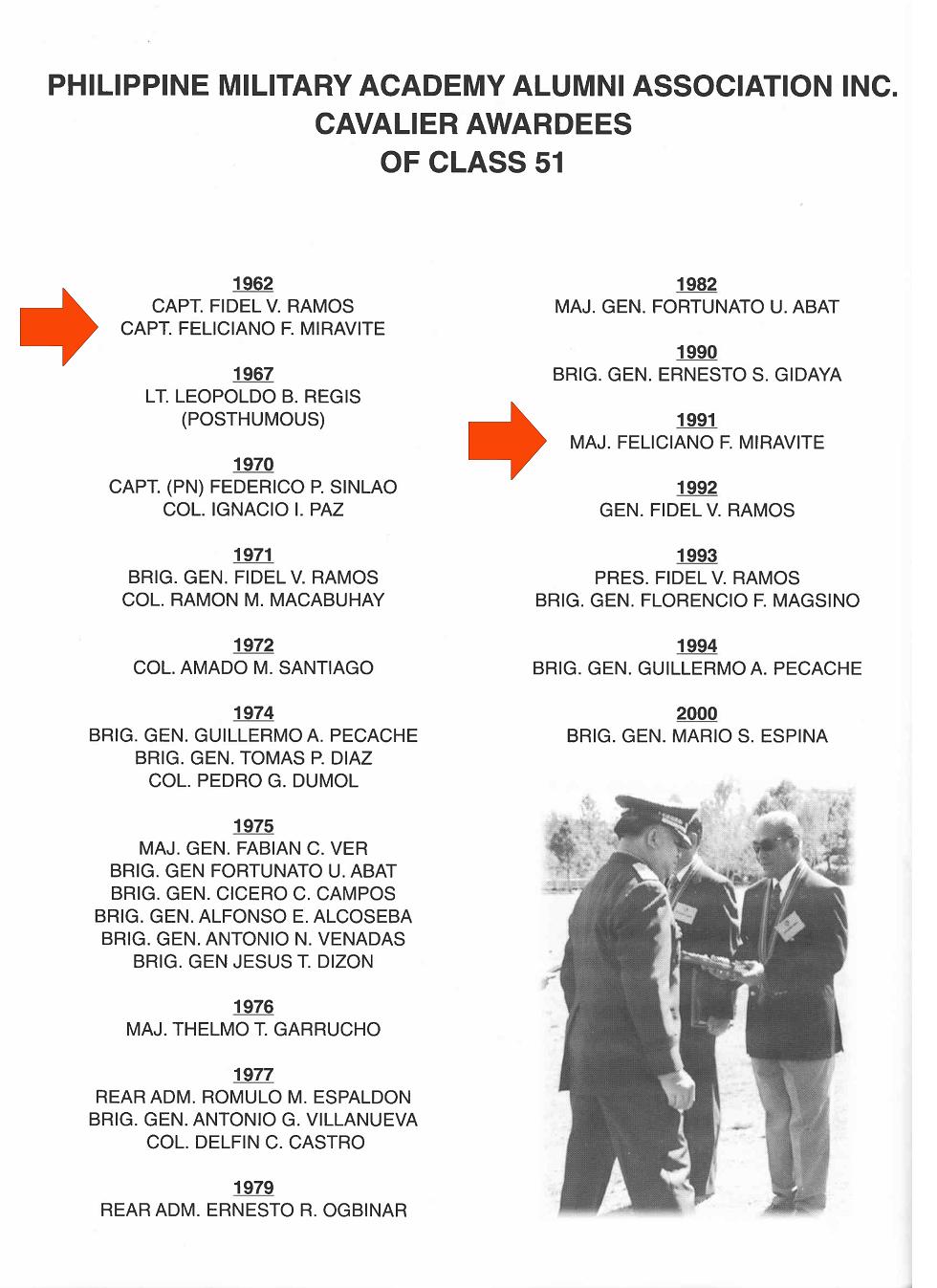

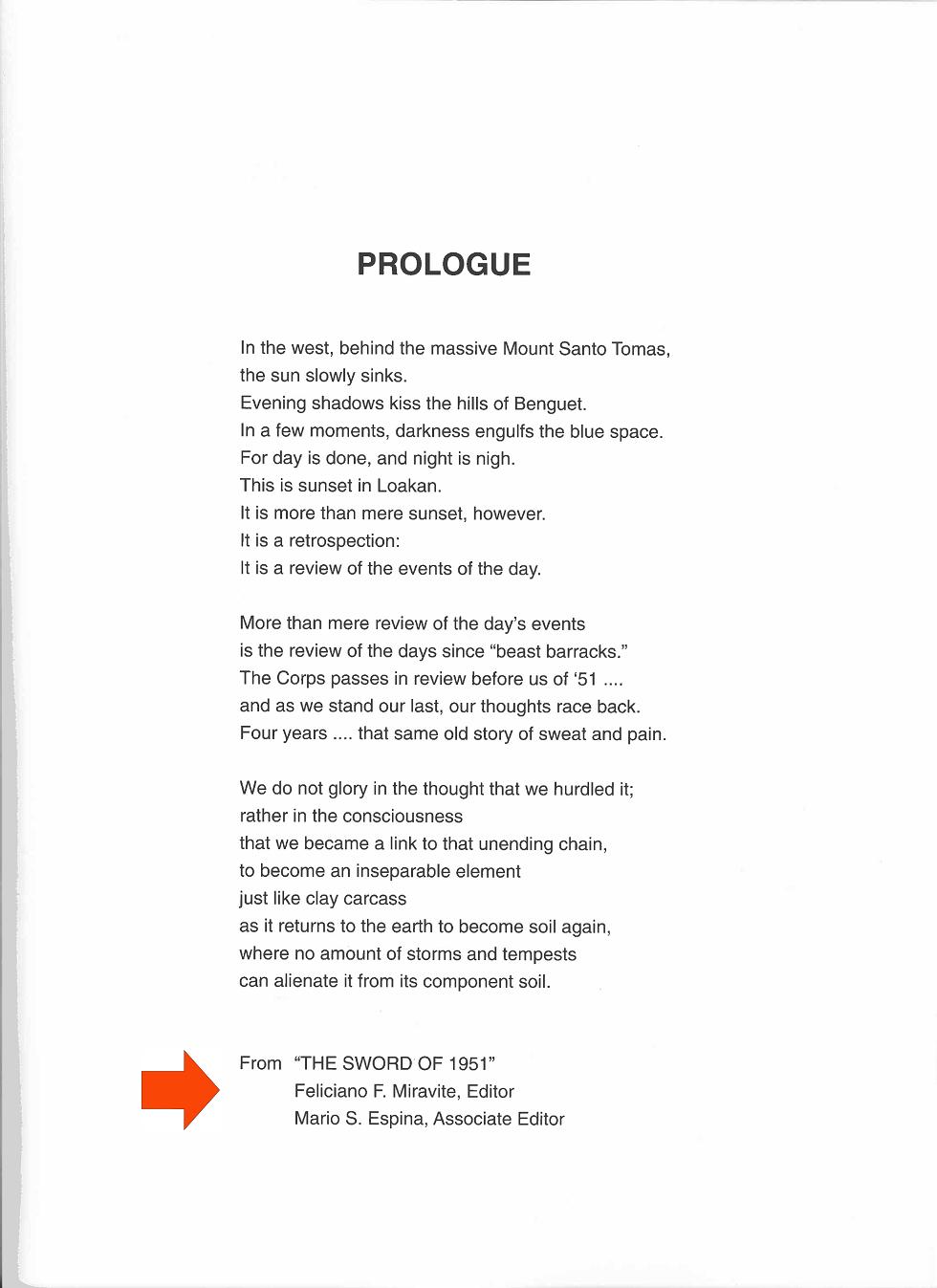

During his cadet days, he was the Editor-in-Chief of THE CORPS and the PEEMAYER in his yearling year and the Editor-in-Chief of THE SWORD when he was a Firstclassman. (from The Golden Sword of PMA Class 1951)

Cabatuan.com

|

|