Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

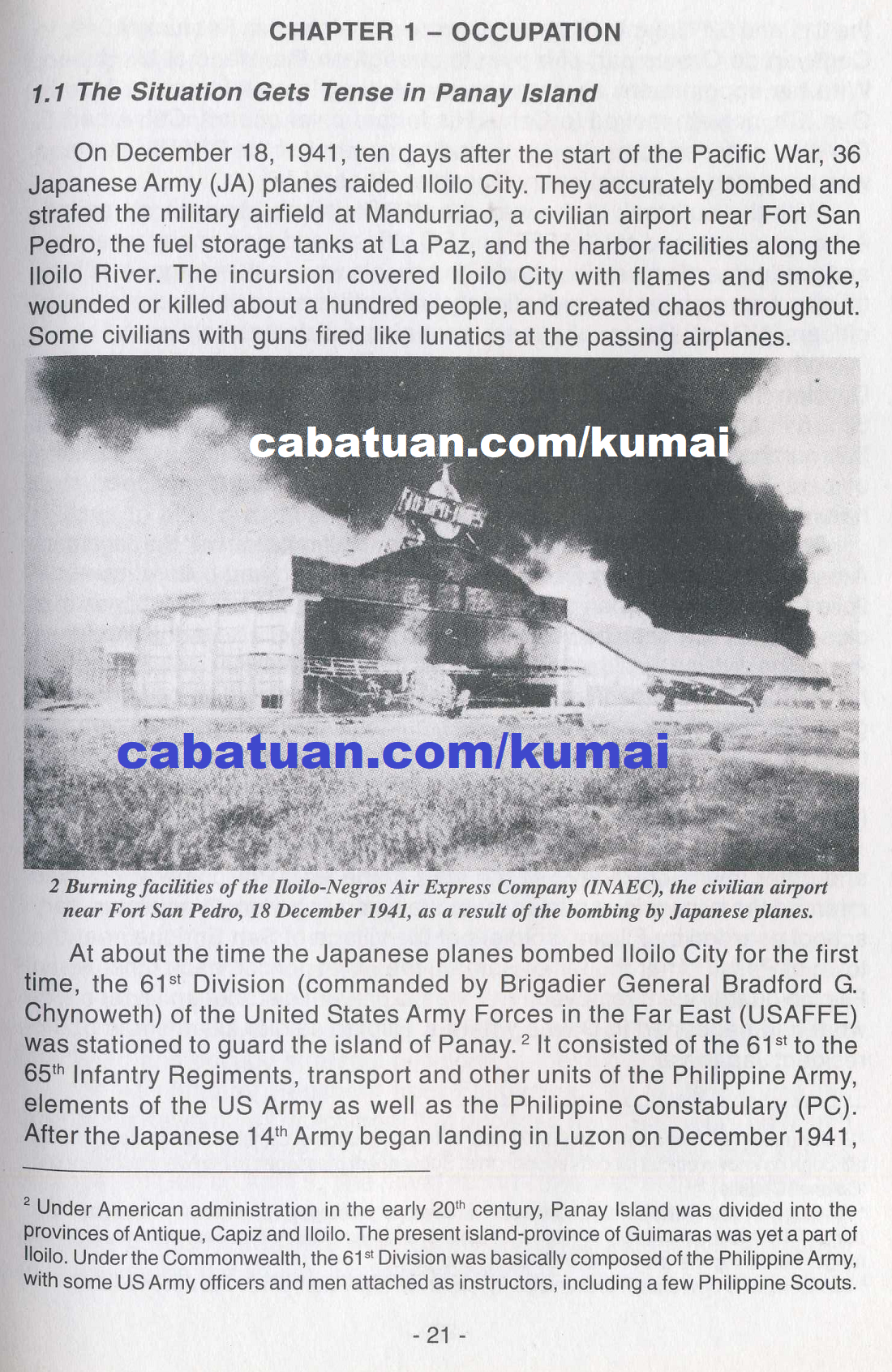

Burning facilities of the Iloilo-Negros Air Express Company (INAEC), the civilian airport near Fort San Pedro, 18 December 1941, as a result of the bombing by Japanese planes. Page 21.

|

|

CHAPTER 1 – OCCUPATION

1.1 The Situation Gets Tense in Panay Island

On December 18, 1941, ten days after the start of the Pacific War, 36 Japanese Army (JA) planes raided lloilo City. They accurately bombed and strafed the military airfield at Mandurriao, a civilian airport near Fort San Pedro, the fuel storage tanks at La Paz and the harbor facilifies along the Iloilo River. The incursion covered Iloilo City with flames and smoke, wounded or killed about a hundred people, and created chaos throughout. Some civilians with guns fired like lunatics at the passing airplanes.

At about the time the Japanese planes bombed Iloilo City for the first time, the 61st Division (commanded by Brigadier General Bradford G. Chynoweth) of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) was stationed to guard the island of Panay. It consisted of the 61st to the 65th Infantry Regiments, transport and other units of the Philippine Army, elements of the US Army as civil as the Philippine Constabulary (PC). After the Japanese 14th Army began landing in Luzon on December 1941, the 61st and 62nd Infantry Regiments were dispatched, in February 1942, to Cagayan de Oro as part of a plan to strengthen the island of Mindanao. With his appointment as commander of the Visayas forces in March, Gen. Chynoweth moved to Cebu. His former chief of staff, Col. Albert F. Christie, succeeded as the commanding general of the 61st Division and was promoted as probationary Brigadier General.

With the outbreak of the war, the 61st Division’s strength increased. Although composed of USAFFE and PC officers and men, many reservists and graduates of universities and high schools who had undergone military training were mobilized as probationary junior officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Other volunteers were also enlisted as soldiers.

When the Japanese Army landed on Panay in April 1942, the 61st Division under Colonel Christie had about 8,000 men organized into the 63rd, 64th and 65th Infantry Regiments, and one provisional regiment. Of this number, only a few were Americans who were mostly high-ranking officers. The division was not well trained and was poorly equipped, and had no artillery.

Thus, the 61st Division decided to avoid any confrontation with the Japanese Army. It planned to bomb Panay’s political, economic and cultural center–Iloilo City and other urban centers as well as vehicles like trucks, buses and cars–as part of a ‘scorched earth’ policy, to prevent their use by the Japanese Army. The division would retreat to the hills around Mount Baloy (1,728 meters high). Should the Japanese Army defeat them, they would go on fighting as guerrillas. The division stored weapons, ammunition, food and fuel, even rice mitts, in the mountains east of Mount Baloy. In early April, the division headquarters moved from Iloilo City to a village called Misi in Lambunao, Iloilo (about 48 kilometers north of lloilo City).

There were around 470 Hôjin (resident Japanese civilians) in Iloilo City and other towns of Panay. At the start of the war, Philippine authorities interned them in various places, eventually moving them to an elementary school guarded by Filipino soldiers at the village of San Enrique near the town of Passi. After the fall of Bataan, the Hôjin policed each other when Filipino guards were removed. This was to prevent disorder and a repeat of what had happened in Davao where a Filipino soldier killed some of the resident Japanese.

On the day of the Japanese landing in Panay, April 16. 1942, the morning edition of the Panay Times carried anti-Japanese articles. The editorial affirmed: ‘It may be a matter of days before the Japanese Army will invade Panay. Japan’s success in the war on Luzon was due to the Japanese Army’s commandeering and using automobiles.’

|

|