Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

Governor Tomas Confesor. Page 26.

|

|

1.2 The Japanese Army Lands In Panay

The Imperial Japanese Army dispatched the 14th Army to the Philippines under the command of Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma. The 14th Army had estimated the enemy force in Panay to be made up of two infantry regiments and one artillery regiment. As with other islands of the Visayas area, the Japanese Army had neither a workable knowledge of the shape and other circumstances nor any proper military topography of the island of Panay. It only had fragments of information on the enemy situation obtained through spies. These circumstances made it impossible for them to plan a detailed campaign. Hence, the Japanese Army only had a general outline for their movement into the Visayas. Operating forces were to decide on the details of the campaign on Panay upon their landing on the island.

With the capture of Corregidor came the plans for the invasion of the Visayas and Mindanao areas. Accordingly, from among the incoming reinforcing troops, the Japanese Army directed to Panay the Kawamura Detachment from the 5th Division that had completed the occupation of Singapore, along with the Kawaguchi Detachment of the 18th Division that had been involved in the takeover of the island of Cebu. Major General Saburo Kawamura, commanding the 9th Infantry Brigade, was assigned as overall commander.

According to the plans of Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo, the Kawamura Detachment was to carry out the operation under the command of the 14th Army until mid-May. Then, together with the Kawaguchi Detachment, it would move to operations in New Caledonia. Notably, these plans presumed that these forces would speedily engage and subdue the USAFFE in Panay and Cagayan de Oro on the island of Mindanao and occupy strategic positions in these two islands.

The 41th Infantry Regiment from Fukuyama City in Japan was the core of the Kawamura Detachment that departed from Singapore on March 27. Escorted by Destroyer Division 24 of the Japanese Navy, they arrived at Lingayen Gulf on April 5. The naval escort consisted of the flagship, the light cruiser Kuma, three destroyers, a torpedo boat, and an auxiliary seaplane carrier. It was here where army and naval authorities concluded agreements on the Panay landing operation.

The main force was to land on the coast west of lloilo City, and a detachment was to land at a beach near Capiz. A force was to occupy the San Remigio copper mine in the province of Antique following a strong recommendation from the Japanese Military Administration (JMA) or Gunsei Kambu in Manila. Under General Kawamura’s command, the 33rd Independent Infantry Battalion (110) headed by Lieutenant Colonel Yasumi Senô was to serve as the Panay garrison. Hence, a portion of this battalion was ordered to land at San Jose, Antique. The 33rd IIB was one of four battalions belonging to the 10th Independent Garrison unit that accompanied the Kawamura Detachment to occupy the Visayas.

|

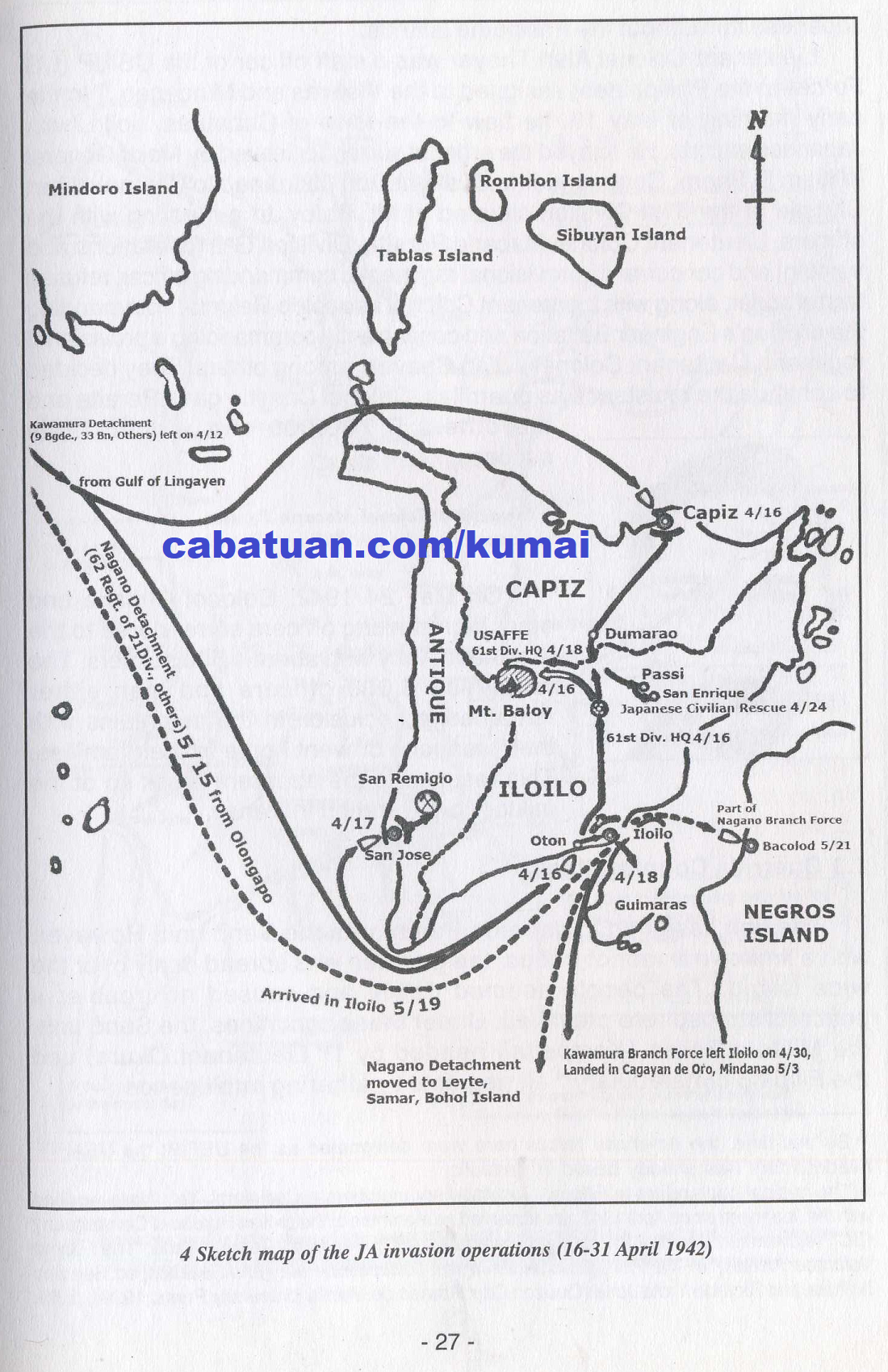

Sketch Map of the JA Invasion Operations (16-31 April 1942). Page 27.

|

|

The Kawamura Detachment, on board ten transports in a convoy escorted by Destroyer Division 24, sortied from Lingayen on April 12 and, in one line, headed south. Two days after its departure, the radio announced news of the Kawaguchi Detachment’s successful landing in Cebu. On April 14, while off Mindoro, a section of the convoy broke off to head east for Capiz.

At 2 a.m. of April 16,1942, the main convoy anchored off the village of Trapiche near the town of Oton, 13 kilometers west of Iloilo City. There was not a flicker of light on the coast, the coconut grove was dark and one could only see the stars in the sky. The convoy caught the enemy by surprise and not even a single shot was heard. The landing force boarded their landing craft in darkness and went ashore. By dawn, all the forces were ashore and landing operations were completed. Then, the forces bound for Iloilo City marched into the Oton town center.

Also before dawn on April 16, a unit of the detachment (the 2nd Company of the Seno unit, or the Takayema unit as it was sometimes called) landed without bloodshed in Baybay, three kilometers north of the town of Capiz. Soon Japanese troops occupied the provincial capitol while the main strength of the forces headed south along the main road towards lloilo City.

On news of this development, the Filipino soldiers carried out their plans. They set fire to the stores on the main streets of Iloilo City as well as sugar warehouses along the Iloilo harbor area. Finally, after having blown up the bridge that separated Jaro and La Paz from the city, they retreated into the mountains inland. Amidst the smoke and fire, local residents evacuated from the city in great confusion. Poor residents who remained became violent looters and bandits, breaking into and ransacking residences and shops in Chinatown, before eventually withdrawing from the city.

The Japanese invasion forces split into two at Oton. The main strength of the Kawamura Detachment headed north while elements of the Seno unit–the 3rd Company (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Jôdo Takahashi) and 4th Company (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Matao Asahi)–entered Iloilo City later that morning.

The central area of Iloilo City that included the Chinese business district was razed and was still burning. The fire was likely to spread further and no one could do anything to stop it. Burnt electrical posts and wires lay on the roads, making it impossible for vehicles to pass. Fire had consumed the warehouses along the waterfront and the acrid smell of the scorched sugar scattered over the road filled the air.

The Japanese Army, led by light tanks, entered the city and proceeded to conduct mopping-up operations (sotô). However, the face of the enemy was nowhere to be found. When the Japanese forces gathered in front of the church by the city’s plaza, the soldiers shouted three cheers (banzai) while the city was engulfed in dazzling flames, dark smoke and the sweet sour odor of burnt sugar. There were no electric lights, no water in the city of Iloilo that night.

In the evening of the 16th, the front line units of the main strength of the Kawamura Detachment that had headed north from Oton advanced to the town of Lambunao, 48 kilometers north of Iloilo City. On the next day, the 17th, the detachment charged north and south like a tempest through the Iloilo plain and reached Dumarao, Capiz, 30 kilometers south of the capital town. Also on April 17th, the 1st Company of the Senô unit (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Osamu Nonomura) landed at Hamtic, south of San Jose. Antique. Facing no resistance, they occupied the town of San Jose. On April 18, an element of the detachment landed across the Iloilo Strait into the northern portion of Guimaras Island.

|

Lieutenant Colonel Macario Peralta, commander of the 6th Military District. Page 28.

|

|

The Karvarnura Detachment took over the central plains of Iloilo and attacked the Iloilo-Capiz national road and surrounding plain on April 23. Before this, on April 18th, there had been an encounter between elements of the Karvamura detachment and the USAFFE’s 1st Battallon of the 63rd Infantry Regiment led by Captain Juliarr Chaves at Mount Dila-Dila, some 20 kilometers west of the town of Calinog. Although the battle was close to the main USAFFE position, the Japanese Army retreated without attempting any attack. Thus undisturbed, the USAFFE forces at Mount Dila-Dila, became the core which the Panay Guerrillas would emerge. In the meantime, the Commonwealth Civil Government of the Province of Iloilo, led by Governor Tomas Confesor, was reorganized for resistance upon its retreat to the mountains of Bocari, Leon, Iloilo.

On April 21, the Light Tank Force led by Second Lieutenant Nakane rescued the Hôjin interned at San Enrique. With their release, the conquest of Panay by the Kawamura Detachment was completed. The forces assembled in Iloilo City on April 25; and after the Hôjin gave souvenirs to the heroes of Singapore. The detachment left for Cagayan, Mindanao on April 30. Some of these men were later wiped out when transferred to Eastern New Guinea and Leyte.

Under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Yasumi Senô. The 33rd IIB of the 10th Independent Garrison unit took control over Panay Island. The battalion lacked equipment and training. On the other hand, the guerrillas were already organized about this time and were beginning to attack.

On the same day that the Japanese arrived, April 16, a Japanese Army plane made an emergency landing in the mountains near the town of Dingle, Iloilo. Young men from the town of Dumangas captured two crewmembers and took them home after offering them a meal and alcoholic beverages. When drunk, the same young men brutally killed and buried them near a pond. This incident was the first atrocity made on Japanese soldiers.

During the time that the Kawamura Detachment was operating in Panay, the Japanese forces in Luzon had launched a general attack on Corregidor. At Corregidor on May 6, 1942, US Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright surrendered all US and Philippine forces that had been resisting the Japanese throughout the Philippine Islands.

Lieutenant Colonel Alan Thayer was a staff officer of the USFIP (US Forces in the Philippines) assigned to the Visayas and Mindanao. In the early morning of May 19, he flew to the town of Cabatuan, Iloilo, with Japanese escorts. He relayed the order of surrender issued by Major General Willlam F. Sharp, Commander for Visayas and Mindanao to Colonel Alben Christie of the 61st Division situated at Mt. Baloy. In a meeting with the officers, Lieutenant Colonel Macario Peralta, Division G-3 (operations and training) and concurrently provisional regimental commanding officer, refused to surrender, along with Lieutenant Colonel Leopoldo Relunia, commanding the division’s Engineer Battalion and concurrently commanding a provisional regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Julian Chaves, among others. They decided to continue the resistance as guerrillas. Colonel Christie gave Peralta and the others P700,000 and wished them success.

On May 24, 1942, Colonel Christie and other high-ranking officers surrendered to the Japanese Army with about 1,800 soldiers. The remaining 6,000 officers and men either remained in seclusion in the mountains with their weapons or went home to their families. This resulted to the apparent break-up of the military organization in Panay.

|

|