Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

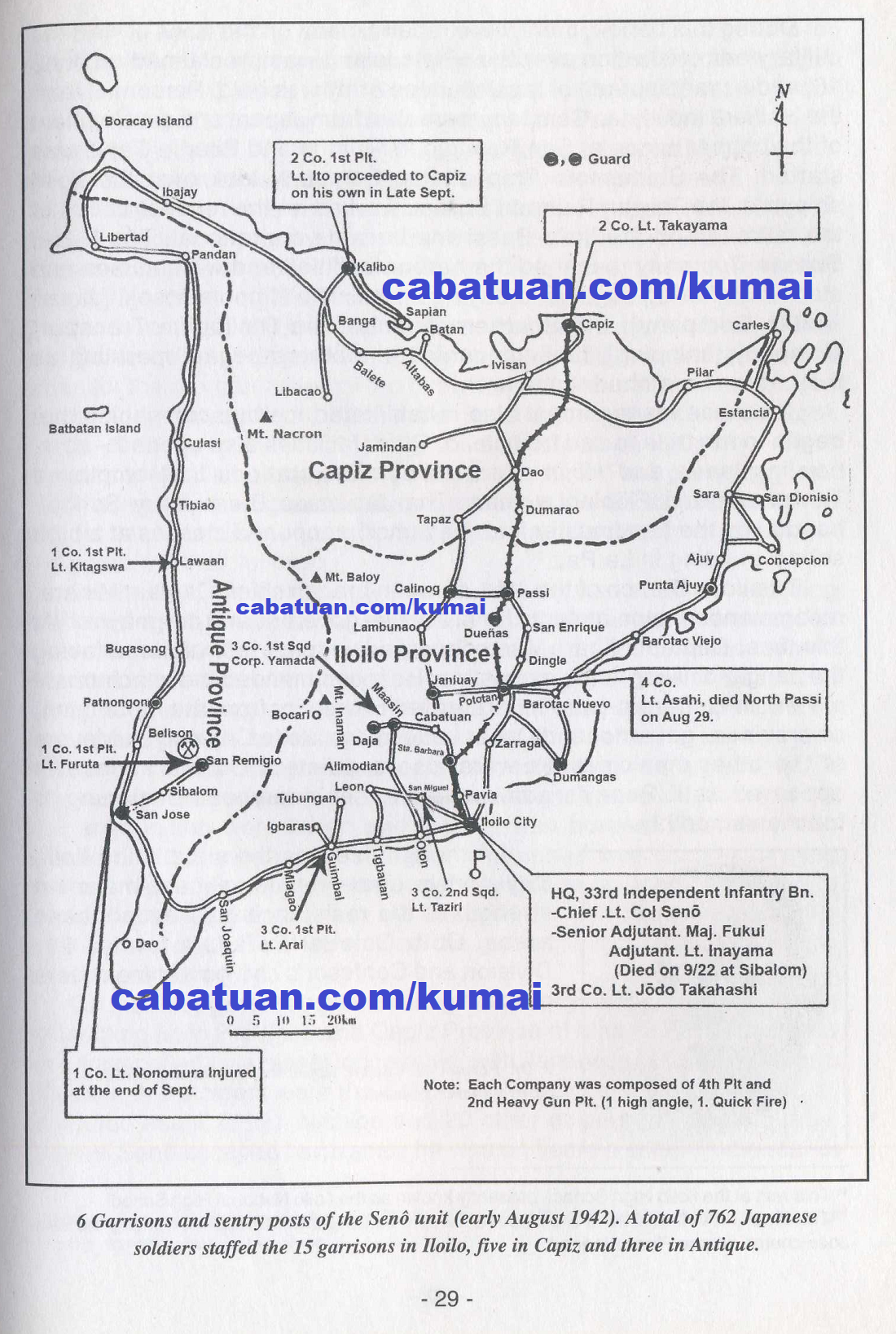

|

Garrisons and Sentry Posts of the Seno unit (early August 1942). A total of 762 Japanese soldiers staffed the 15 garrisons in Iloilo, five in Capiz and three in Antique. Page 29.

|

|

1.3 Guerrilla Counterattacks

The unit assigned to garrison Panay was the Senô unit. However, with a limited number of troops, the garrison was spread thinly over the wide island. The people seemed docile and caused no trouble: a peaceful atmosphere prevailed. Under these conditions, the Senô unit, the Military Police (Kempeitai) headed by 1st Lieutenant Okura, and the Filipino constabulary all neglected gathering intelligence during this period, there were repairs made on the ruins of war; the military administration over the whole island was proclaimed on June 16 and a grand parade of the Japanese Army was held. Personnel from the Ishihara Industries Company were sent from Japan, and development of the copper mines at San Remigio in Antique and Pilar in Capiz was started. The Shimamoto Shipbuilding Company took over the Iloilo shipyard; the Taiwan Railroad Bureau worked on the reconstruction of the railroad and the Iloilo-Passi line became operational. The Mitsui Bussan Company managed the harbor facilities and warehouses and started gathering sugar and buying copra. The Nippon Eoseki (Japan Textile Company), The Southern Airlines, the Philippine Transport Company (shipping), fuel companies and others began operating as they were dispatched to the area.

Japanese management also rehabilitated the bus companies that began to run trips to and from Iloilo. Other facilities also opened – bars, bowling lanes and Hôjin-operated comfort stations that employed Taiwanese and Filipino women. The Japanese Elementary School, headed by the headmaster Isao Kayamori, reopened classes at a high school building in La Paz.

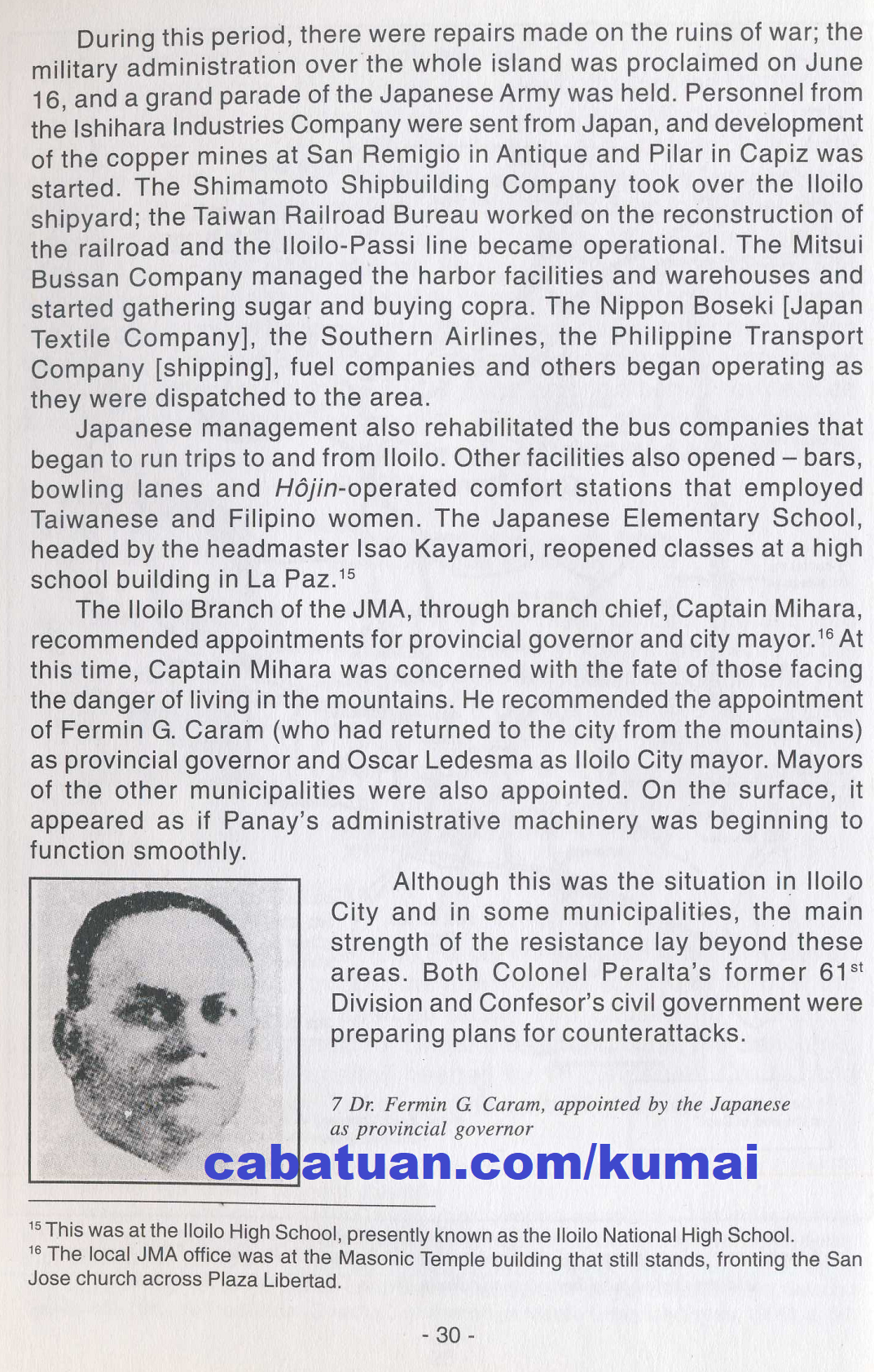

The Iloilo Branch of the JMA, through branch chief Captain Mihara, recommended appointments for provincial governor and city mayor. At this time, Captain Mihara was concerned with the fate of those facing the danger of living in the mountains. He recommended the appointment of Fermin G. Caram (who had returned to the city from the mountains) as provincial governor and Oscar Ledesma as Iloilo City mayor. Mayors of the other municipalities were also appointed. On the surface, it appeared as if Panay’s administrative machinery was beginning to function smoothly.

Although this was the situation in Iloilo City and in some municipalities, the main strength of the resistance lay beyond these areas. Both Colonel Peralta’s former 61st Division and Confesor’s civil government were preparing plans for counterattacks.

Early in June 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Peralta judged that the time for the reorganization of the resistance forces was good. Leaving the Agtugas Mountain near Calinog with 15 subordinates, he issued General Order No. 1 on June 10 to announce the formation of the Panay Free Forces with himself as the head. Within several days, he gathered around 2,000 former officers and men as well as other volunteers under his command.

|

Dr. Fermin G. Caram, appointed by the Japanese as provincial governor. Page 30.

|

|

Initially, while the island was in a state of anarchy, Lieutenant Colonel Peralta made it a priority to control the looters and bandits. With the cooperation of the police forces of the “free” civil government, they thoroughly contained the troublemakers. By the end of July, peace and order was restored and the local residents trusted Peralta’s military forces and Confesor’s civil government. They openly held dance parties to raise funds for the reorganization of the guerrilla forces and offered its soldiers and food. Neither the Senô unit nor the Kempeitai took notice of these activities. In August 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Senô reported to Manila headquarters “peace and order in Panay is quite good.”

The reorganized guerrilla forces restarted the fire of resistance on August 24 . According to guerrilla histories, guerrilla attacks in the middle of August were as follows:

On the 24th, the Calmay garrison in Janiuay was attacked, resulting in the killing of 20 Japanese soldiers and 1,000 rounds of ammunition taken. Governor Confesor’s brother, Patricio Confesor, waited for and attacked two trucks with Japanese soldiers near the base at Cabatuan, killing 10 and taking one truck. In Bitaogan, Passi, a train operated by the Japanese was assaulted and derailed. In Dueñas, a car carrying residents collaborating with the Japanese Army was ambushed. A Japanese soldier and all of the civilian passengers were killed. Weapons and ammunition were taken and the car was burned. Guerrillas also attacked the Dueñas garrison and ambushed two trucks carrying reinforcements. Fortunately, the Japanese troops on board were able to escape from the trucks. Other units attacked by guerrillas were the sentry post at the Jalaur River as well as the garrisons at Calinog and at the outskirts of Iloilo City.

On the 29th, guerrillas placed two boxes of dynamite on the train line connecting Iloilo Province and Capiz Province at Man-it, Passi, and blew train pulled by a diesel locomotive, with Japanese soldiers on board. (Killed in this incident were the Senô unit’s 4th Company commander, 1st Lt. Matao Asahi, 2nd Lt. Nishibe and 20 other officers (shôko) and men. Colonel Senô escaped harm since he was on board a coach in the rear of the train, some distance from the explosion). The guerrillas carried out many attacks and ambushes on other garrisons. The Senô unit suffered from many who were killed and wounded; they also lost many arms and ammunition. To provoke the people’s hatred and anger against the Japanese and to boost their fighting spirit, some guerrillas displayed the heads of Japanese who were beheaded in the town plazas.

During this period of guerrilla attacks, Japan’s war situation in the Pacific War received severe shocks. In the Battle of Midway on, June 5, the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers and one heavy cruiser, along with 3,500 casualties that included the best pilots of the navy. On August 7, American forces landed on Guadalcanal, and heavy fighting spread widely. Superior American forces pressured the Japanese Army to retreat.

Guerrilla attacks in Panay continued in September 1942 and the violence increased. Around 120 Japanese soldiers moving on the road south of Dueñas were ambushed by guerrillas on September 2nd. That same day, Japanese soldiers were also attacked at Banga-bante, north of Zarraga town (18 kilometers northeast of lloilo). On September 3, guerrillas raided the Japanese garrison sentry post at Malitbog. Calinog, as well as the sugar central at Janiuay. On September 5, the Pototan garrison received a huge assault followed by continuous fighting. On September 6, guerrillas assaulted the Maasin garrison, the sentry post at the Daja water reservoir (three kilometers west); they also wiped out the Janiuay garrison. The Santa Barbara garrison, 20 kilometers north of Iloilo City, was attacked on the same day, and the fighting here lasted for one week. On the 22nd, two trucks carrying Japanese soldiers were ambushed at Igtagmay, Sibalom in Antique (Adjutant Inayama of the 1st company, serving as representative of the commanding officer, was killed in action in this encounter).

|

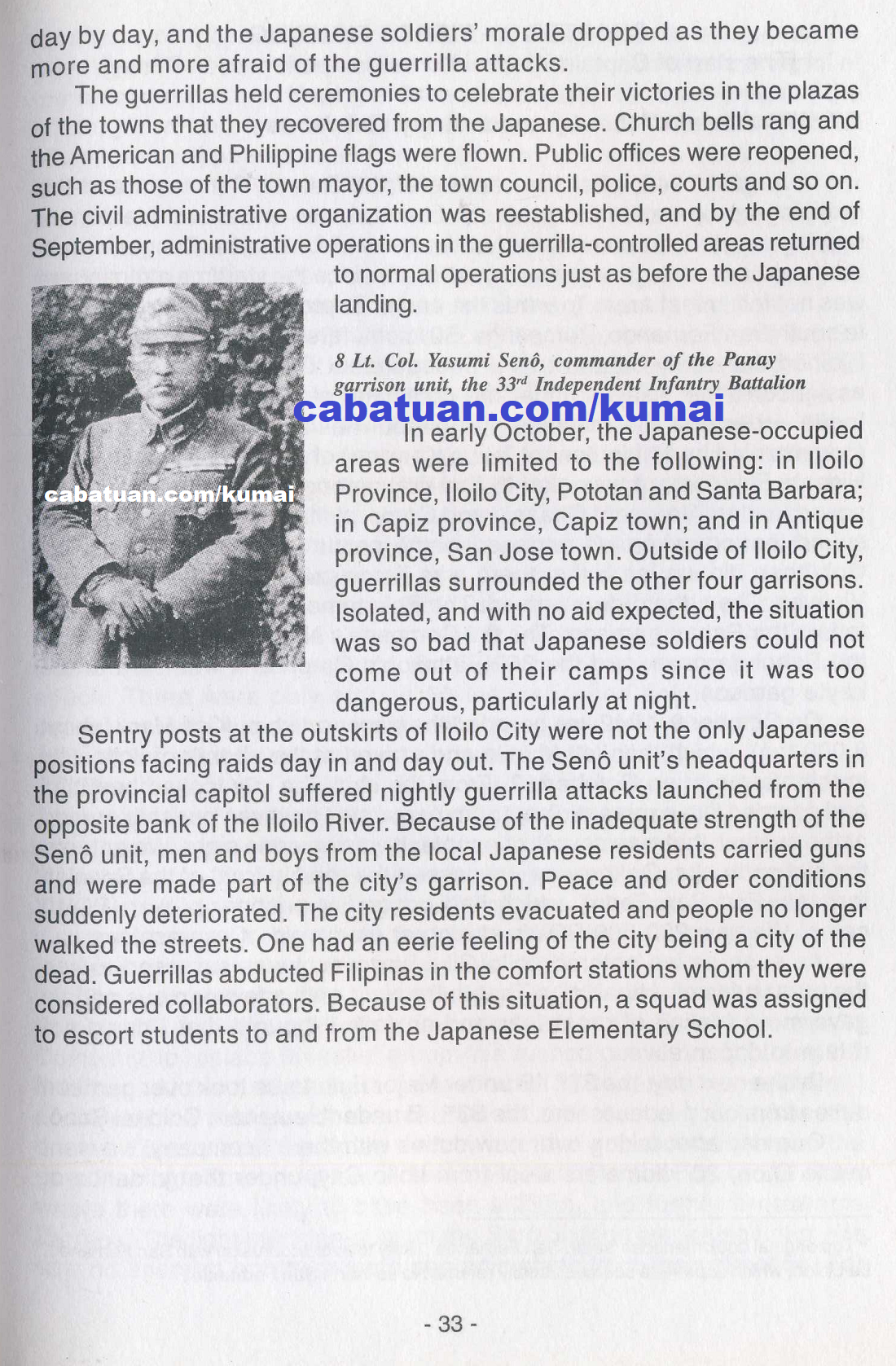

Lt. Col. Yasumi Senô, commander of the Panay garrison unit, the 33rd Independent Infantry Battalion. Page 33.

|

|

In October, the guerrilla attacks continued. On October 4, the Sentry post at Mataraus Hill in Patnogon. Antique garrison was attacked. On October 5, the garrison of Capiz. Capiz–then held by the 2nd Company or the Takayama unit–was also attacked. (At about this time the Kalibo garrison in Capiz province–commanded by 1st Lieutenant Ito–withdrew without orders). The guerrillas not only attacked garrisons but also frequently attacked the sentry posts near Iloilo City itself. Gunshots could often be heard within the city.

The Senô unit barely made up one battalion, one that was hurriedly mobilized and dispatched to the front lines in the South. Because of the situation, the unit suffered increasing numbers of dead and wounded. The garrisons also repeatedly withdrew. Damages increased day by day, and the Japanese soldiers’ morale dropped as they became more and more afraid of the guerrilla attacks.

The guerrillas held ceremonies to celebrate their victories in the plazas of the towns that they recovered from the Japanese. Church bells rang and the American and Philippine flags were flown. Public offices were reopened, such as those of the town mayor, the town council, police, courts and so on. The civil administrative organization was reestablished, and by the end of September, administrative operations in the guerrilla-controlled areas returned to normal operations just as before the Japanese landing.

In early October, the Japanese-occupied areas were limited to the following: in Iloilo Province, Iloilo City, Pototan and Santa Barbara: in Capiz province, Capiz town; and in Antique province, San Jose town. Outside of Iloilo City, guerrillas surrounded the other four garrisons.

Isolated, and with no aid expected, the situation was so bad that Japanese soldiers could not come out of their camps since it was too dangerous, particularly at night.

Sentry posts at the outskirts of Iloilo City were not the only Japanese positions facing raids day in and day out. The Senô unit’s headquarters in the provincial capitol suffered nightly guerrilla attacks launched from the opposite bank of the Iloilo River. Because of the inadequate strength of the Senô unit, men and boys from the local Japanese residents carried guns and were made part of the city’s garrison. Peace and order conditions suddenly deteriorated. The city residents evacuated and people no longer walked the streets. One had an eerie feeling of the city being a city of the dead. Guerrillas abducted Filipinas in the comfort stations whom they were considered collaborators. Because of this situation, a squad was assigned to escort students to and from the Japanese Elementary School.

|

|