Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

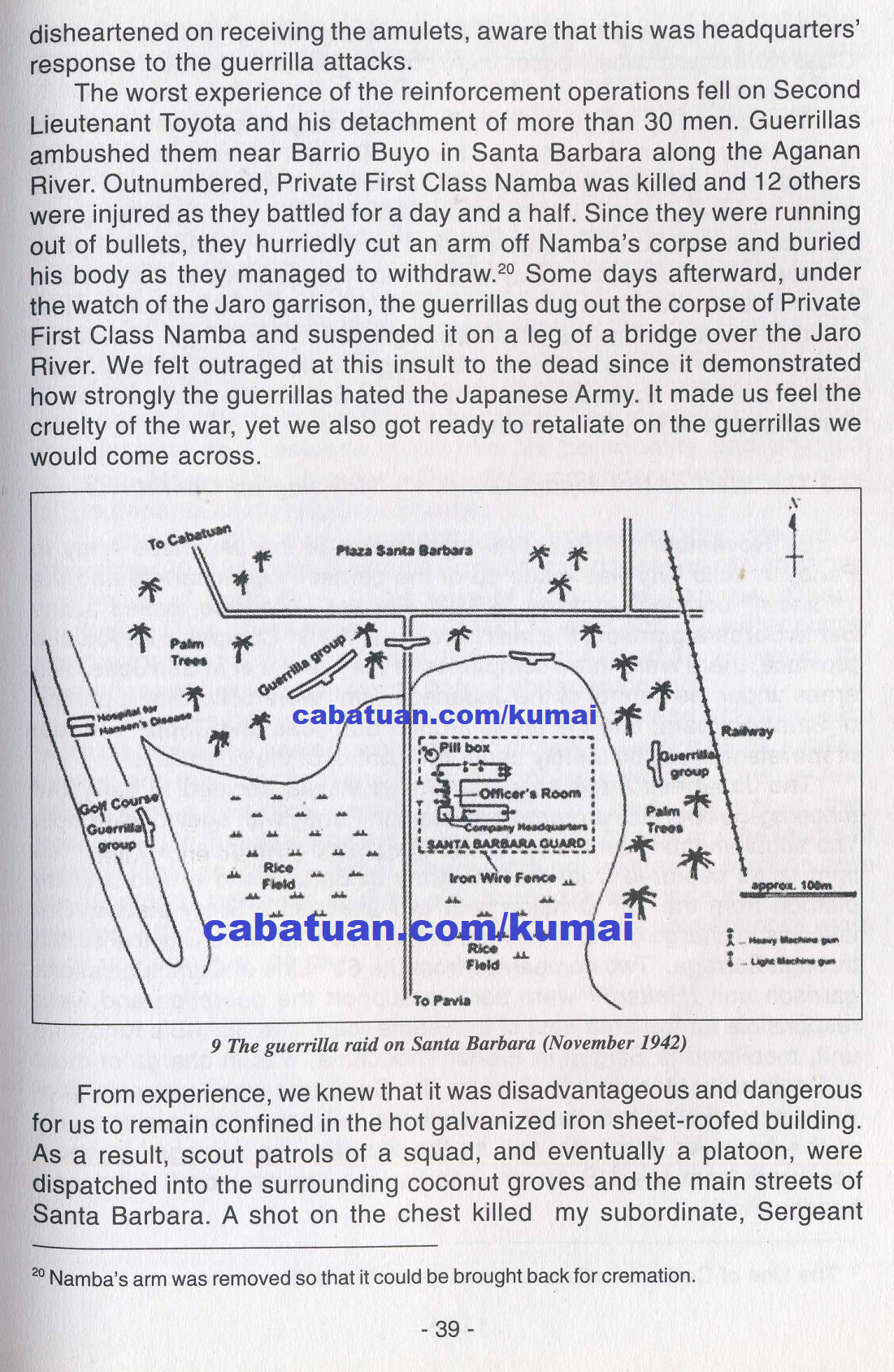

The Guerrilla Raid on Santa Barbara (November 1942). Page 39.

|

|

2.2 Seige of the Santa Barbara Garrison

The Pototan withdrawal heightened the troops’ fears of the guerrillas and caused the deterioration of the unit’s morale. The next assignment of the Kawano unit of the 3rd Company, to which I belonged, was to replace the occupying forces at the Santa Barbara garrison. We did that in late October without any guerrilla attack. The garrison was at a former elementary school in Santa Barbara, 20 kilometers north of lloilo City. The Concrete school building was along the main road. There was an athletic field on the east, rice fields to the south, a coconut grove 60 meters to the north and northwest, and a plateau on the west where a golf curse and a leprosarium were located. It was the last remaining Japanese garrison of the Seno unit outside of lloilo City and, inevitably, a primary target for the guerrillas.

Before dawn, one day early in November, two heavy machine guns set at the garrison’s main gate suddenly started to fire. We heard voices of the enemy on the road between the shooting and we jumped to our position in our underwear. The attack lasted for days. In the tropical climate, corpses deteriorated after half a day. Therefore, we cremated the bodies at the school grounds at night

under enemy fire. The enemy was thus aware of the casualties we sustained. We sent daily reports of the results to the battalion headquarters and they reluctantly decided to send reinforcements to the garrison. A detachment led by the unit commander himself left Iloilo for the relief of Santa Barbara. This was made up of 250 soldiers from the headquarters–the 1st Company and a platoon led by Second Lieutenant Toyota of the 3rd Company.

However, guerrillas ambushed the relief force between Pavia and Santa Barbara, killing nine mud-covered soldiers, including the veteran Sergeant Gunji. Despite serious damage, the relief force managed to reach the Garrison. On seeing the unit commander in mud-covered boots, the armed guard at the main gate hurriedly saluted him. Major Fukutome shouted. ‘How dare you! It is dangerous for me when you salute like that. It tells the enemy that I am the commander!’ Anxious and broken down with fear and fatigue, he collapsed into the chair at the company commander’s office. He was in no condition to either listen to our report or be appreciative of our service. Seeing the commander of the Panay garrison in such shape made me feel desperate aboul the future.

Soon after, NCOs (kashikan) and soldiers (heishi) of the 1st Company hastily staggered into the garrison shouting. ‘Creosote, creosote!” Mud was all over them. Evidence of the fierceness of their encounter. The company had attacked the guerrillas on the plateau west of the main road and pushed on until they reached the leprosarium. At the hospital, the combat-weary and thirsty soldiers quickly drank from water containers. The Filipino patients tried to stop them. calling out, ‘Leper, leper!’ However, the soldiers only realized the significance of their warning after they had drank water from those containers. That was why they wanted creosote to wash out what they had just taken in.

Later on. Major Fukutome told them, ‘Since there is not enough manpower, I will not he able to come so often to reinforce your defense. You yourselves should take courage and perform your duty. He then distributed Shinto medallion charms to each of the officers. We were disheartened on receiving the amulets, aware that this was headquarters’ response to the guerrilla attacks.

The worst experience of the reinforcement operations fell on Second Lieutenant Toyota and his detachment of more than 30 men. Guerrillas ambushed them near Barrio Buyo in Santa Barbara along the Aganan River. Outnumbered, Private First Class Namba was killed and 12 others were injured as they battled for a day and a half. Since they were running out of bullets, they hurriedly cut an arm off Namba’s corpse and buried his body as they managed to withdraw. Some days afterward, under the watch of the Jaro garrison, the guerrillas dug out the corpse of Private First Class Namba and suspended it on a leg of a bridge over the Jaro River. We felt outraged at this insult to the dead since it demonstrated how strongly the guerrillas hated the Japanese Army. It made us feel the cruelty of the war, yet we also got ready to retaliate on the guerrillas we would come across.

From experience, we knew that it was disadvantageous and dangerous for us to remain confined in the hot galvanized iron sheet-roofed building. As a result, scout patrols of a squad, and eventually a platoon, were dispatched into the surrounding coconut groves and the main streets of Barbara. A shot on the chest killed my–subordinate, Sergeant

Okazaki, the bravest member if the company along with Private First Class Komamura. Most houses were burned down and the local residents had run away.

The attacks by the guerrillas became less frequent; but when they did so from time to time, they attacked fiercely. The unit commander’s nervous breakdown kept getting worse and he would yell at everybody. Major Fukutome made himself an object of laughter since he had soldiers guard his accommodations. Eventually, fed up with the situation, Captain Watanabe requested the Visayas garrison headquarters at Cebu that a psychiatrist should examine the commander. As a result, the unit commander left Japan for tnree months after his assignment to the 37th IIB. Thereafter, he became an officer attached to the Rikugun Yonen Gakko (Military Youth Academy). In the absence of the commander, Captain Watanabe served as the battalion’s Deputy Commander.

|

|