Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

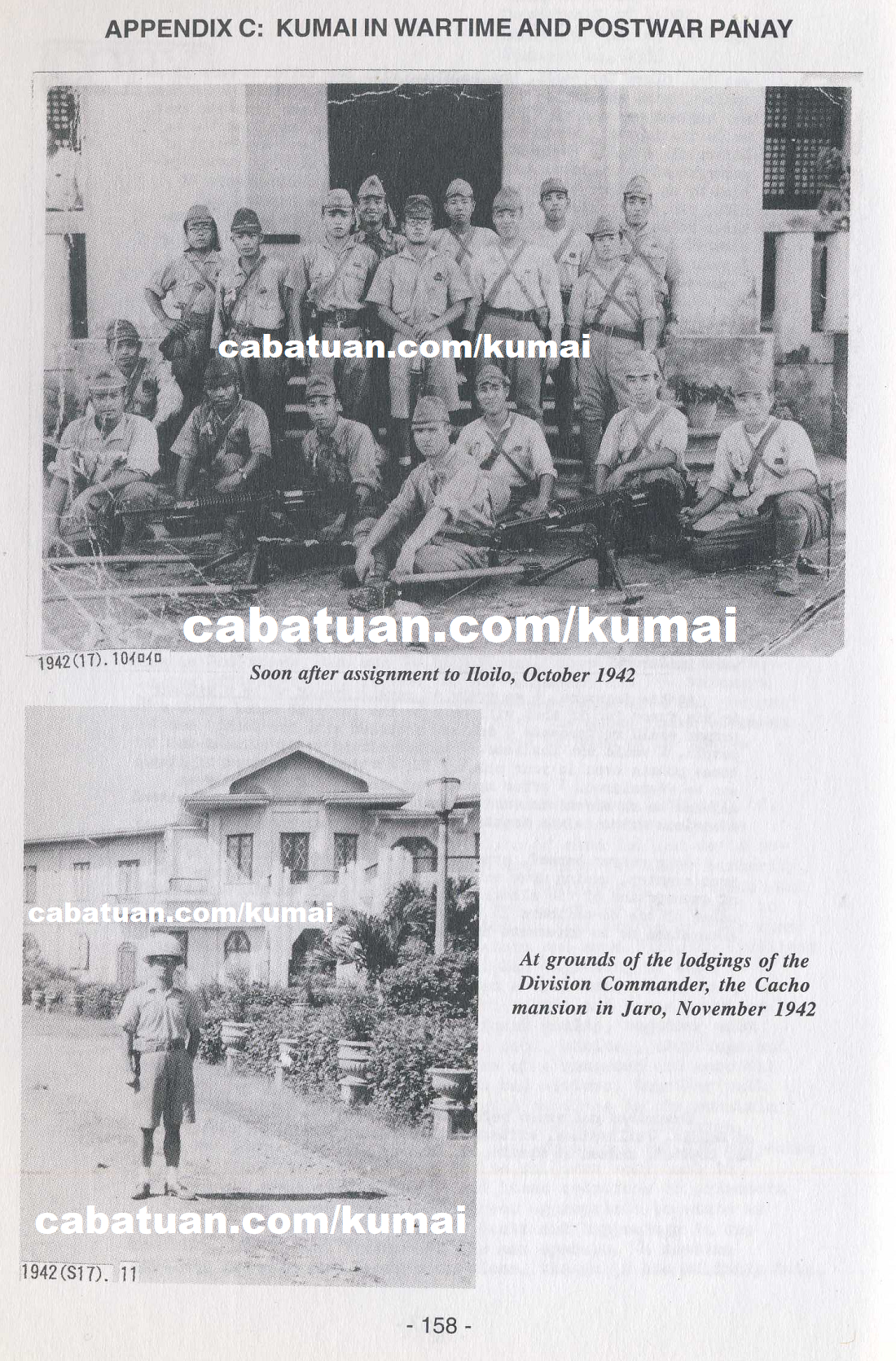

(top) Soon after assignment to Iloilo, October 1942

(bottom) At grounds of the lodgings of the Division Commander, the Cacho mansion in Jaro, November 1942

|

|

5.5 Dark Night Attacks

Staff officer Hidemi Watanabe arrived at New Washington to inspect the area. Learning of the unexpectedly poor results of the campaigns at Tablas and Romblon and witnessing the devastation of New Washington, he seemed determined to attack the guerrillas. He ordered the Tozuka Unit to the central mountainous areas of northern Antique and western Capiz. After five months of the punitive expeditions, members of the Tozuka unit including the commander and Captain Watanabe, felt aggravated at being sent to the most dangerous parts of the island. But it was an order and we could not do nothing about it. We went with heavy hearts. The task was to destroy guerrilla bases along the 150-kilometer route that ran diagonally across Panay. The actual length of the course was more than 300 kilometers. It took us at least 25 days to cross over mostly jungle and steep mountain areas in the midst of the rainy season.

Despite these conditions, the soldiers were in excellent health. Only a few fell ill throughout the months of the expedition. They ate coconut and drank coconut juice as well as ate papaya stems. While on the march, they acquired pigs, chickens, and vegetables; and as soon as they stopped, they cooked a nutritious casserole. Without complaining, they acted upon orders, capturing and executing guerrillas with ease. Just a year before, while first watching water torture administered by a kempei on a guerrilla suspect, they had shouted, ‘Stop it! Stop!’ Now they were changed beings and had become experts at guerrilla subjugation.

Going up the Aklan River and into the mountains near Banga and Libacao in Capiz, we got more information on the guerrillas. One night my subordinates and I came across a few thatch (nipa)-built houses on a plateau. As we silently moved closer, we saw around 10 young men cleaning rice. Instinctively, I knew they were guerrillas; so I ordered my men to surround the house as we climbed up. However, when we were just about 60 meters away, the guerrillas noticed us and fled.

This experience led us to believe that there were indeed guerrillas hiding in the area so we detained local people to get even more information on them. We soon learned there was a company of guerrilla soldiers stationed nearby, which meant that there were at least 100 guerrillas around. My force consisted of only around 30 soldiers. In these mountains, there was no way to contact the unit’s field headquarters. Therefore, I decided to perform a night attack on our own since there was no moon and it was completely dark. I could see that the man guiding us looked so pale and his face was twisted with fear, indicating that he had told us the truth. Suddenly he stopped and pointed to a nipa house that looked like a guerrilla sentry post. I gave orders to the Filipino spy Vicente Morata: ‘Surround the house with the Filipino spies and we Japanese soldiers will encircle you. Call out to them like a friend, and as soon as the door opens, jump in and capture the guerrillas. Do not fire the pistol.’

Morata and three or four Filipino spies approached the hut. Morata said something and the door opened. Morata and the others jumped in with pointed pistols and captured three or four men. The captives had a few rifles and were obviously sentries of the guerrilla forces. An NCO instantly beheaded the captives, except one whom I immediately interrogated: ‘The area is full of Japanese soldiers. If you give me information, I will save your life.’ The frightened guerrilla replied, ‘I am a guard. The main camp of the company is in a few large houses about two kilometers from here. There are three more look-outs along the way.’

With his hands tied behind him, the guard was put in the lead to guide us. About 300 meters down the road, we came across a sinister house. I ordered the guerrilla to identify himself to the house’s occupants. As soon as the door opened, our soldiers captured the few men who were inside. The same NCO again beheaded them right away, except for one.

We thanked him. “We know all about you. Lead us to the next bantay (guard or sentry) house. Identify yourself and we will soon release you.” The terrified guerrilla again was placed in the lead and we proceeded to the next sentry post. Morata and the other Filipino spies repeated the same process and caught the guerrillas.

As we approached the guerrilla base, the soldiers became tense and the guerrilla guide was frightened and shaking. He stopped. Threatening and coaxing him, we advanced through the mud in the dark night until we saw three or four large nipa houses. As the soldiers ran into nearby groves, we heard around a dozen shots and a tracer bullet flashed. We dashed towards the sound of the gunshots and surrounded two big houses. When we jumped in, however, the obvious barracks of the guerrillas was already empty. I judged that it was dangerous to pursue them in the night’s darkness and so we withdrew. Although we overcame the sentry posts, we failed in our attack on the base.

When I reported to Captain Watanabe at the field headquarters, I was furiously reprimanded, ‘Why have you seized only this much weaponry? How dare you report your failure to capture the guerrillas?’

Each unit was engaged in night attacks but the guerrillas were firmly on guard. Acting on information obtained, the Japanese often dashed in only after the guerrillas had fled.

|

|