Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

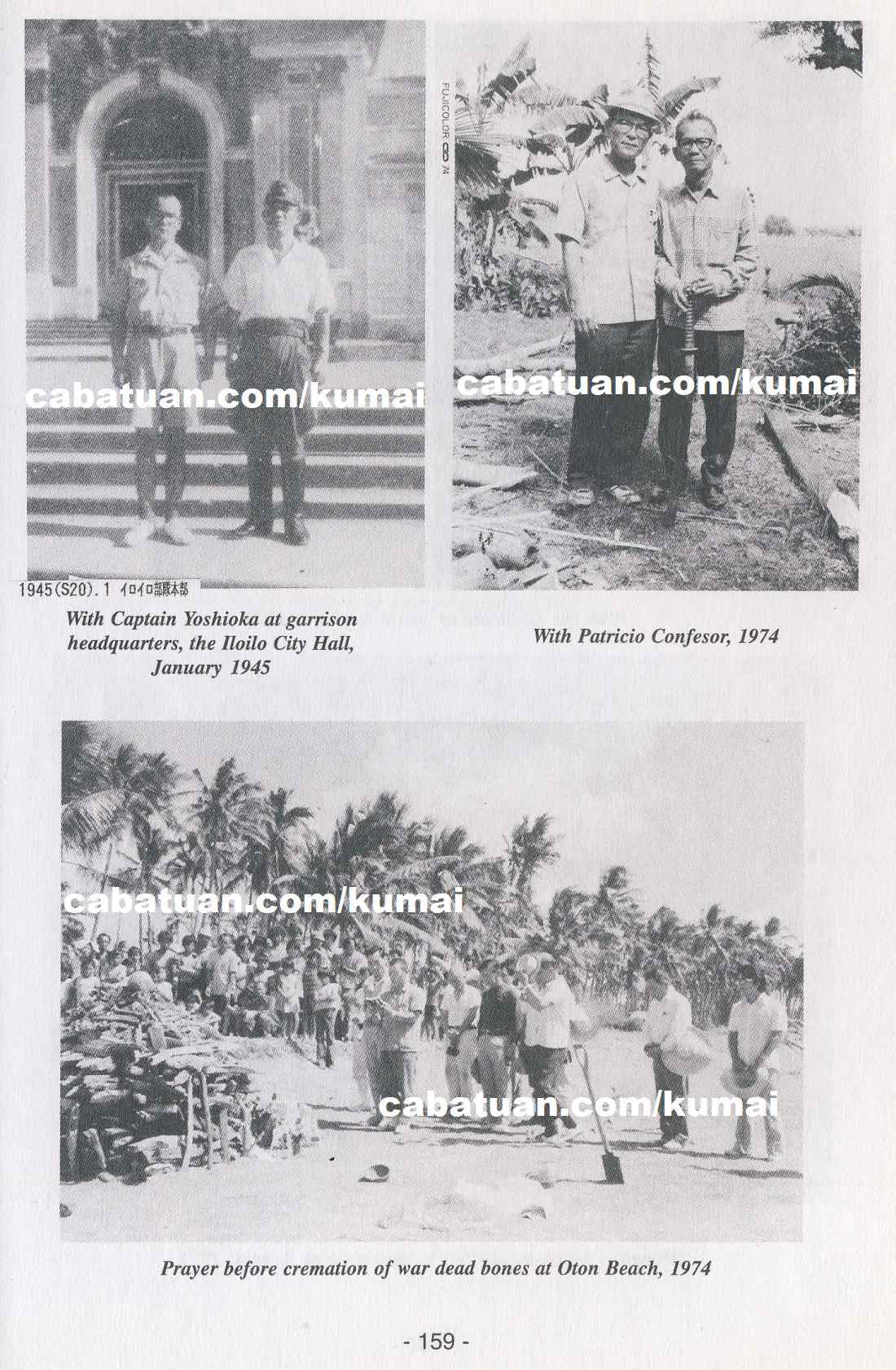

(top left) With Captain Yoshioka at garrison headquarters, the Iloilo City Hall, January 1945

(top right) With Patricio Confesor, 1974

(bottom) Prayer before cremation of war dead bones at Oton Beach, 1974

|

|

6.3 Another Joint Punitive Expedition

Until March 1944, it had been peaceful. Eventually, the guerrillas reorganized themselves and became active once again. They first attacked the Philippine railway trains and buses on the trunk roads. In due course, 1st Lieutenant Toyota’s garrison at Sara, which was situated farthest from the town, had to withdraw because of worsening conditions in the surrounding areas.

In the beginning, the surrendered Deputy Governor from Sara, Jose Aldeguer, cooperated with the Japanese Army but eventually stopped showing up. Other garrisons reported frequent attacks by guerrillas. Since I was in charge of ordnance (armament), one day I received several cartridges from the garrison at Tigbauan. I had never seen such cartridges before in Panay. The diameter was about the same as that of a 38-caliber pistol, but the length was double the size of those bullets. I was told that in spite of the light sound of their shots, they were fired from rifles in rapid succession. Reports on light shooting sounds came in continuously. Eventually, we learned of the new US model of carbines with 20-round cartridges developed for fighting in the jungle. There were also reports of the capture of these rifles. However, as it was against army rules to deliver any confiscated weapons of the enemy to unit headquarters, no one had turned in the captured guns. The carbine was convenient; with a range of around 400 meters and weighing one-third of the Japanese rifle, it was the best rifle for jungle combat.

Due to the increasing reports of guerrilla attacks, headquarters decided to send two companies of the Tozuka unit on an expedition around Mt. Dila-Dila near Calinog and Mt. Baloy where the alleged headquarters of the 61st Division was. By the beginning of April 1944, this ended without particular results as the guerrillas were able to escape. The village in the hills west of Lambunao was torched upon the completion of the operations.

Around this time, there was a massive reorganization of Visayas area units. The 16th Division was transferred to Leyte in mid-April. Lieutenant General Shiro Makino, the commander of this division, became the overall army commander in the Visayas. Soon after, the brigade headquarters gave the order for the Joint Punitive Expedition by army units in Panay and Negros. The goal was to destroy the wireless bases of the guerrillas–there were more than ten in Panay and several in Negros–and to obtain the wireless units.

This was a firm request of the Japanese Navy so that the Combined Fleet could use the Guimaras Strait as their base. They wanted the obliteration of the enemy wireless units to end the detailed reports of their movements to the US. (As I learned after the war, this was part of Operation Sho-go or the Victory Operation of the Combined Fleet. The channel between Panay and Guimaras was one of the front bases of the 1 st Striking Force of the Kurita Fleet.)

The Navy cooperated with the Army by transporting the 16th Independent Infantry Battalion (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Shigeru Nishimura) from Bohol Island to lloilo by cruiser. The operation area of our unit was western Iloilo and Antique, the Nishimura unit was in eastern lloilo, and the Tanabe unit was in eastern Capiz.

Major General Takeshi Kôno set up the expedition headquarters at Iloilo City. The expedition took around 60 days, from early May towards the end of June 1944. The special punitive expedition company was organized within the Tozuka unit with 1st Lieutenant Fujii as company commander. I was the unit’s deputy commander and was in charge of intelligence.

The first mission was to seize the wireless radio of the 61st Division guerrilla headquarters at Mt. Dila-Dila and Mt. Baloy. During a fierce battle with a group of the guerrillas, their headquarters must have fled towards the direction of Antique. Near Mt. Baloy, we captured the children of a guerrilla officer: a bright girl who held a three-year-old boy in her arms, and three or four other younger brothers squatting at her feet. After an enormous effort to alternately soothe and threaten the girl, she finally told me that her father was Major Eriberto Castillon, the former head of the Civil Affairs Unit of the 6th Military District.

We also located an abandoned US-made wireless unit that measured 70 cm X 40 cm and weighed 12 kilograms. For three nights and four days we hunted for this small and light-weight radio, putting our lives in danger and undergoing many adversities. With our unit commander, we were all amazed at our luck in finding the portable radio and just kept staring at it. It must have been so easy to land many of such wireless units from a US submarine. It struck us silly that it had taken all three battalions to drag around for the capture of just one of these.

During the expedition, we were also astonished to find a specially printed US propaganda magazine – entitled Free Philippines – in a remote mountain village. On its cover was a portrait of MacArthur with the Stars and Stripes and the words “I Shall Return.” There was also the latest issue of Life Magazine. Among the photos in those magazines was one from New Guinea, in which many Japanese soldier corpses were lying on the beach while MacArthur, with a corncob pipe in his mouth, inspected the battlefields. There were photos of enormous tanks and aircraft as well as those that showed how the different the uniforms and equipment of US soldiers had become from those used in the battles in Bataan. It made us doubt our capacity to win against the US forces with their vast and excellent weaponry. We knew that the US forces were sending in by submarine propaganda materials and ammunition, not to speak of large numbers of radios. We also became wary of the intelligence capabilities of our headquarters. Given these realities, we wondered if the Navy and Army headquarters had been serious in ordering the capture of the wireless radios.

We climbed down the mountains with Nicky, the youngest Castillon boy, carried on the shoulder of a medical sergeant Nakamura. I left all the children with Governor Caram at lloilo City. The older sister Thelma and her father, Major Castillon himself, kindly wrote petition letters while I was imprisoned at Sugamo.

|

|