Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

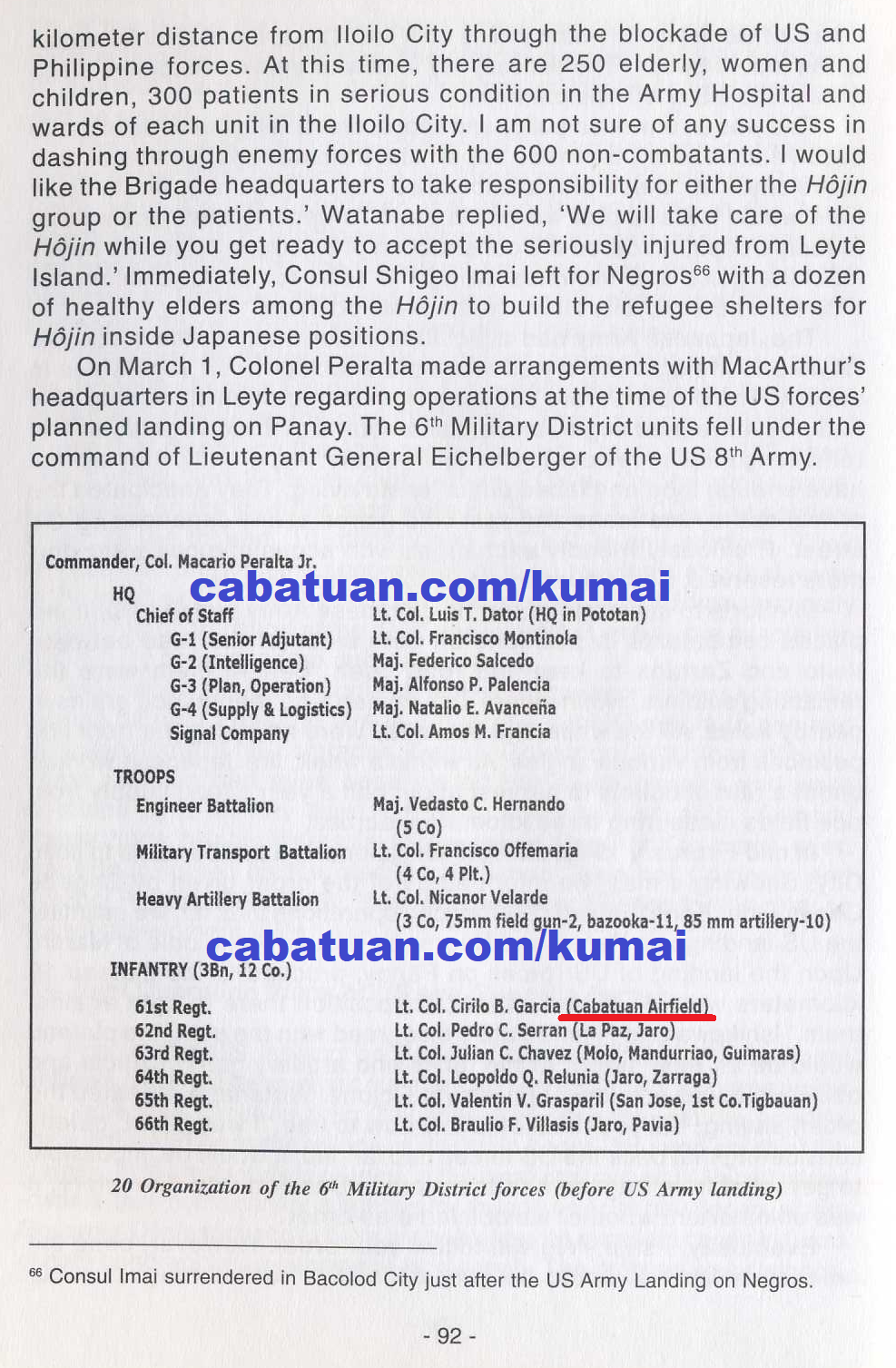

Organization of the 6th Military District forces (before US Army landing). Page 92.

|

|

7.4 Joint Operation Plans of US and Guerrilla Forces

Prior to the US landing on Panay, Colonel Tozuka, 1st Lietutenant Ishikawa and I had reexamined our plans and agreed on the following policy. The Japanese forces in Iloilo City should all dash through the guerrilla siege lines and go to the village of Bocari in Leon – situated south of Mt. Inaman, in the mountainous region in the west-central part of Panay Island – where they could continue fighting for as long as possible. Bocari, where Governor Confesor used to have his base, was an excellent haven in terms of both geographical strategy and food supply. The problem was distance. It was 22 kilometers on a straight line from Iloilo City to the town of Alimodian at the foot of Bocari. The difficulty lay in how to break through the siege lines of the US and Filipino armies.

This was an unwritten policy and kept secret among the three of us. To deceive the enemy, we made superficial preparations for a last stand in the city. With these preparations, we hoped that the guerrilla spies here would believe that we would stay. To deceive both enemy and friendly troops, I ordered the construction of pillboxes, bases for heavy machine guns and trenches along the road for about a kilometer between the Iloilo City Hall and the Molo position.

The Japanese Army had difficulties under the guerrilla blockade. While under siege, there was a complete lack of fresh vegetables in the city. The soldiers were suffering from malnutrition since they only had rice, unrefined sugar, and small amounts of dried vegetable. The remaining Filipino residents also looked pale. Apparently, they did not have enough food and faced difficulty surviving. They anticipated the arrival of the Americans and cast cold glares at any Japanese on the street. Previously friendly exchanges with acquaintances were now more reserved. Some even avoided conversing with us.

In efforts to secure food for the Japanese Army and the Hôjin, we placed combatants in positions on both sides of the road between Iloilo and Zarraga to keep the road open. Behind them were the remaining soldiers, Hôjin elders and women who reaped rice grains in nearby fields. All the while, the guerrillas were attacking the front line positions from various angles. All within a week, the Japanese worked under a rain of bullets to harvest about half a year’s food supply from rice fields measuring three kilometers across.

In mid-February 1945, staff officer Colonel Watanabe came to Iloilo City. Showing a map, he informed us of the order given by Brigade Commander KGno: ‘Based on American operations thus far, we estimate the US landings on Panay and Negros by around the middle of March. Upon the landing of US forces on Panay, proceed to the plateau 10 kilometers west of Alimodian, set the position there to fight against them.’ Ishikawa and I immediately disagreed with the plan; the plateau would be an easy target of the tanks and artillery guns. Critical and oblivious to our opinions, Lieutenant Colonel Watanabe repeated the order, saying, ‘All you think of is just how to flee.’ I was silent, quietly considering that once the US forces had landed, it would be impossible to get relief from brigade headquarters in Bacolod City. Therefore, it was unimportant whether we obeyed their order.

Eventually, I said, ‘We will follow your order. However, once the Americans land, it would be very difficult to rush through the 30-kilometer distance from Iloilo City through the blockade of US and Philippine forces. At this time, there are 250 elderly, women and children, 300 patients in serious condition in the Army Hospital and wards of each unit in the Iloilo City. I am not sure of any success in dashing through enemy forces with the 600 non-combatants. I would like the Brigade headquarters to take responsibility for either the Hôjin group or the patients.’ Watanabe replied, ‘We will take care of the Hôjin while you get ready to accept the seriously injured from Leyte Island.’ Immediately, Consul Shigeo lmai left for Negros with a dozen of healthy elders among the Hôjin to build the refugee shelters for Hôjin inside Japanese positions.

On March 1, Colonel Peralta made arrangements with MacArthur’s headquarters in Leyte regarding operations at the time of the US forces’ planned landing on Panay. The 6th Military District units fell under the command of Lieutenant General Eichelberger of the US 8th Army.

Upon returning to Panay on March 4, Colonel Peralta issued an order to all officers and men:

In the event of an American landing, the mission of this Command is to prevent any Japs from escaping into the hills. Each regimental commander will therefore take appropriate steps to ensure that his area is covered so as to prevent the enemy from breaking thru and giving us another headache. We have already succeeded in fixing him to isolated areas and we shall continue to do so.

Until an American landing, it is our mission to give the enemy no rest. He must be worn down physically and morally. We will continue harassing him to the extent that our resources will permit. Where possible, we shall attack with a view to killing as many Japs as possible.

From early March, a US Martin flying boat appeared over Iloilo City twice a day, obviously reconnoitering in preparation for the landing. By March 15, the promise of staff officer Hidemi Watanabe about taking charge of the Hôjin was not realized. Attacks by the guerrillas in Jaro became fiercer such that the tracer bullets in the night sky over Iloilo City looked like a fireworks festival. The sheer amount of the bullets first surprised the Japanese Army. However, on the night of March 17, the shooting mysteriously ended.

|

|