Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

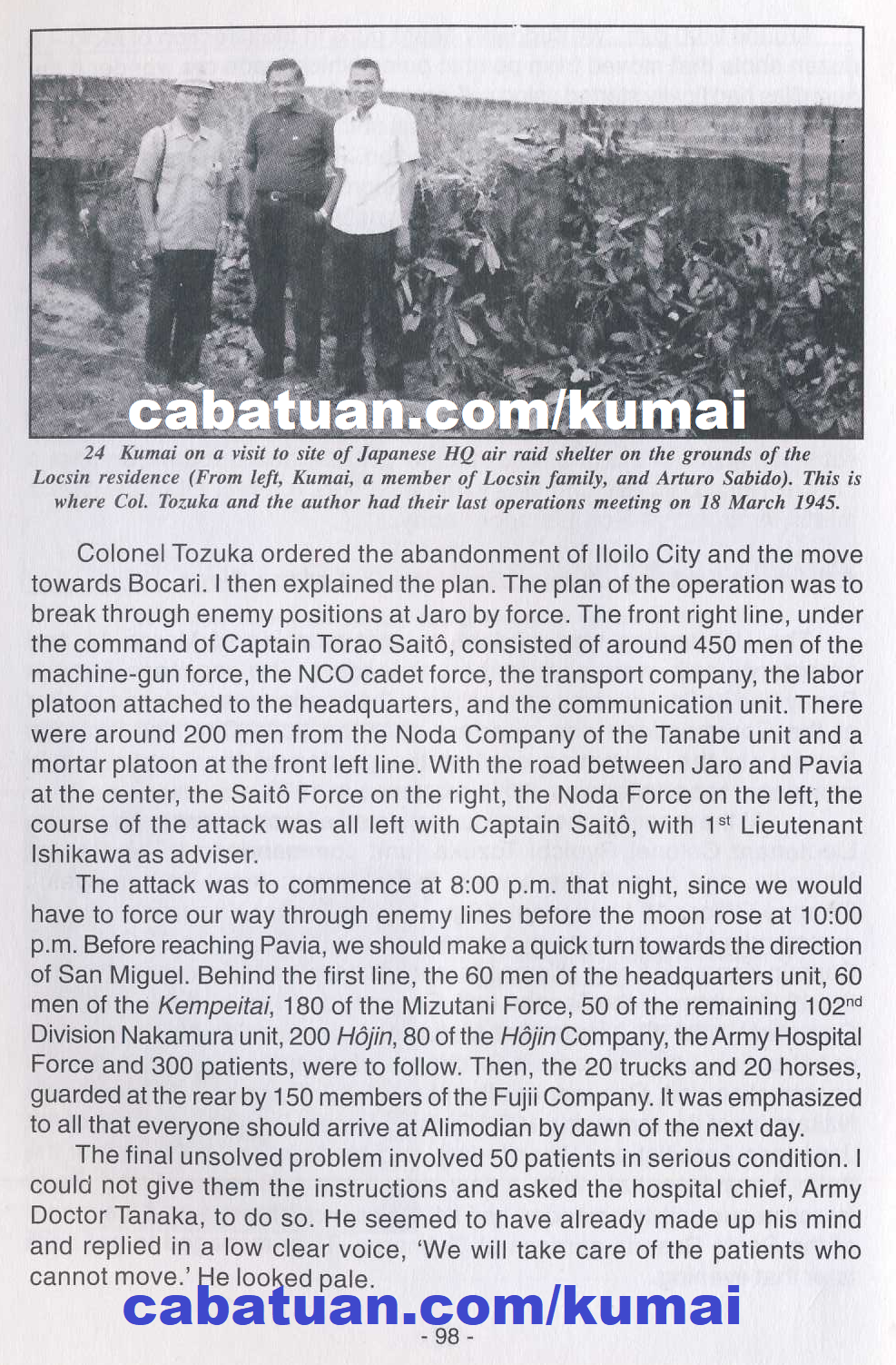

Kumai on a visit to site of Japanese HQ air raid shelter on the grounds of the Locsin residence (From left, Kumai, a member of Locsin family, and Arturo Sabido). This is where Col. Tozuka and the author had their last operations meeting on 18 March 1945. Page 98.

|

|

8.2 Fierce Fighting at Jaro: Breaking Out of the Siege

The US landing was evident on that morning of March 18 and emergency calls were sent to the unit leaders. The Japanese Army in Panay had its final operations meeting at the headquarters’ air raid shelter at the Commander’s new quarters near the Iloilo City Hall in Molo. Previously the swimming pool at the garden of the Locsin family residence, the shelter was still in existence in 1973.

At the meeting, the headquarters staff all looked tense. Apart from Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka (unit commander). 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa, and myself, there were the following: Army Doctor Egami, Finance Officer 1st Lieutenant Kuge, 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto (deputy commander of the machine-gun force), Lieutenant Fujii of the 2nd Company, Captain Kaneyuki Koike (Kempeitai commander), and Lieutenant Noda of the 1st Company of the Tanabe unit, Commander Suzuki of the Transport Company, and 1st Lieutenant Mizutani (commander of the oil tank construction unit), a captain in charge of engineering of the airfield construction unit, Commander Ika of the Hôjin Company, 1st Lieutenant Nakamura of the remaining 102nd Division forces, President Kimura of the Japanese Association (Nihonjin-kai), and Medical Doctor Tanaka of the Iloilo Army Hospital. With a few dozen men, Captain Torao Saitô (machine gun unit commander) had left the previous night to lead the retreat of the Santo Rosario garrison at Guimaras. They managed to get back later that evening.

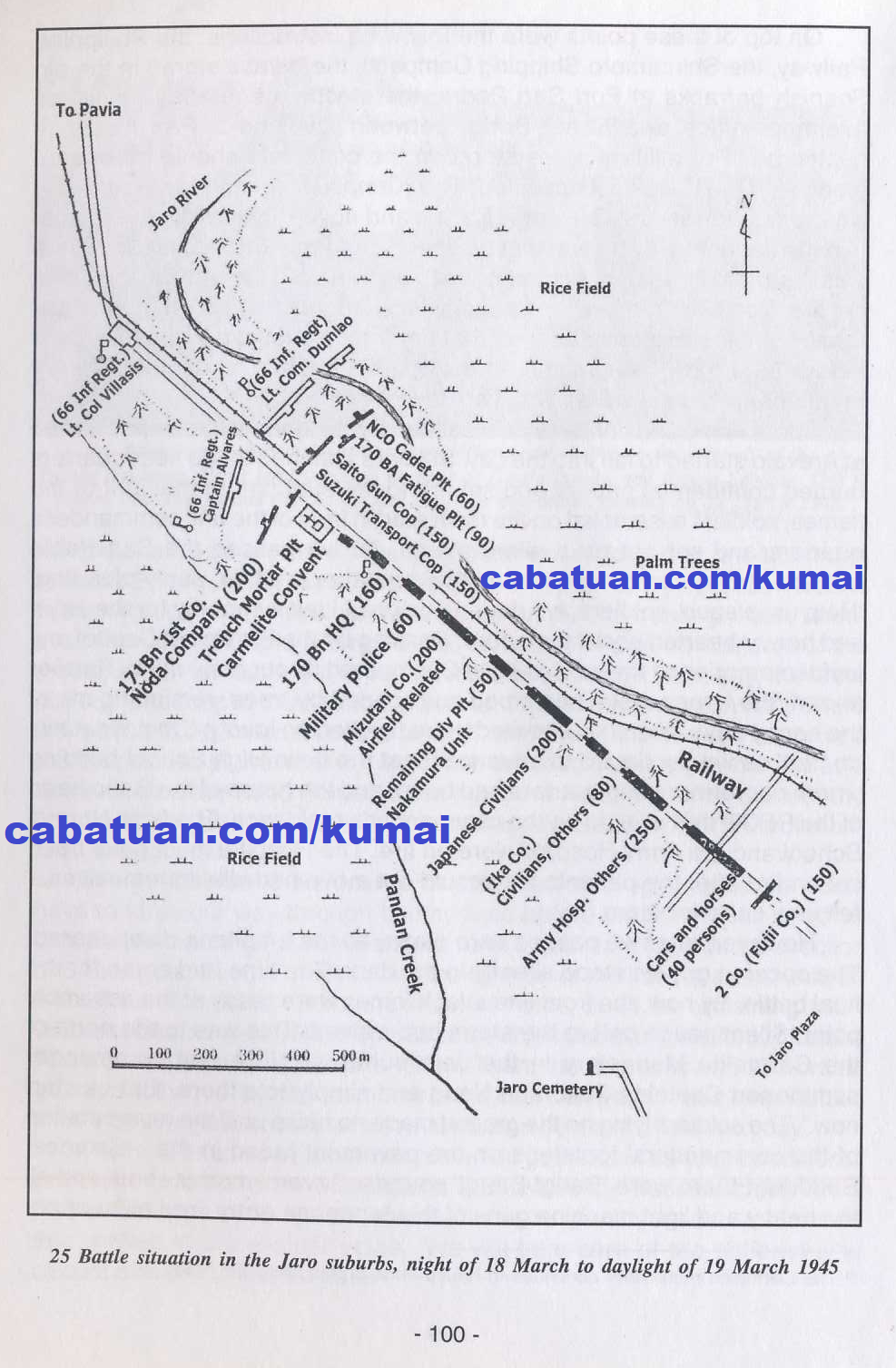

Colonel Tozuka ordered the abandonment of Iloilo City and the move towards Bocari. I then explained the plan. The plan of the operation was to break through enemy positions at Jaro by force. The front right line, under the command of Captain Torao Saitô, consisted of around 450 men of the machine-gun force, the NCO cadet force, the transport company, the labor platoon attached to the headquarters, and the communication unit. There were around 200 men from the Noda Company of the Tanabe unit and a mortar platoon at the front left line. With the road between Jaro and Pavia at the center, the Saitô Force on the right, the Noda Force on the left, the course of the attack was all left with Captain Saitô, with lst Lieutenant Ishikawa as adviser.

The attack was to commence at 8 p.m. that night, since we would have to force our way through enemy lines before the moon rose at 10 p.m. Before reaching Pavia, we should make a quick turn towards the direction of San Miguel. Behind the first line, the 60 men of the headquarters unit, 60 men of the Kempeitai, 180 of the Mizutani Force, 50 of the remaining 102nd Division Nakamura unit, 200 Hôjin, 80 of the Hôjin Company, the Army Hospital Force and 300 patients, were to follow. Then, the 20 trucks and 20 horses, guarded at the rear by 150 members of the Fujii Company. It was emphasized to all that everyone should arrive at Alimodian by dawn of the next day.

The final unsolved problem involved 50 patients in serious condition. I could not give them the instructions and asked the hospital chief, Army Doctor Tanaka, to do so. He seemed to have already made up his mind and replied in a low clear voice, ‘We will take care of the patients who cannot move.’ He looked pale.

On top of these points were the following instructions: the Philippine Railway, the Shimamoto Shipping Company, the bombs stored in the old Spanish barracks at Fort San Pedro, the electric generation plant, the telephone office, and Forbes Bridge between Iloilo and La Paz should be , destroyed. The military notes stored in the consulate should be burned along with the building it occupied. The Kempeitai commander, Kaneyuki Koike, was to request Governor Caram and Iloilo City Mayor Ybiernas to join the Japanese Army, but that he should not force them to do so. There was a strict ban against setting houses on fire and killing civilians. ‘Don’t ‘ set fire. Don’t kill. We’re fighting against the US, not against the guerrillas.’ Finally, the instructions stressed that the forces should assemble at Jaro before 8 p.m. The planning meeting adjourned around 5 p.m. By then, enemy planes were flying very low over the city.

|

Battle situation in the Jaro suburbs, night of 18 March to daylight of 19 March 1945. Page 100.

|

|

Soon, explosions of heavy shells fired by the enemy forces positioned at Arevalo started to fall into the city. Soldiers attached to the headquarters burned confidential papers and set fire to the staff car. In the light of the flames, soldiers assembled on the main road in front of the unit commander’s quarters and, set out on a silent march. As we passed the San Pablo hospital, Hôjin women called out to us one after another, sadly pleading, ‘Help us, please, soldiers, we depend on you.’ I felt sympathy for the Hôjin and heavy-hearted about the future. Passing by the Provincial Capitol, my joyful memories of the past in Iloilo City rushed through my mind. Further ahead, the Lopez residence stood surrounded by trees, reminding me of the happy days when I was invited there. I yelled on loudly, ‘Do not set this on fire!’ as we continued to advance, past the Iloilo High School building where our former headquarters had been, and the home of the Cacho head of the PECO that used to be the commander’s residence. The Iloilo Normal School and the Army Hospital were on fire. The Hospital must have been set on fire after the patients who could not move had killed themselves. I felt very sorry for them.

However, after we passed Jaro plaza, all the emotions disappeared. The coconut groves stood silently in the dark. The time had come for the final battle. By now, the front line attack forces were ready at the assembly point. Silent peace before the storm had arrived. This was to the north of the Carmelite Monastery in the Jaro suburbs. The unit commander summoned Captains Saitô and Noda and simply told them, ‘Let us start now.’ The soldiers lying on the ground made no noise until the reverberation of the commanders’ footsteps on the pavement faded in the distance. Suddenly, there were ‘Bang! Bang!’ sounds. Several mortar shots and all the heavy and light machine guns of the Japanese Army fired all at once.

At the same time, just like strong winds and rains, torrents of enemy fire started. Especially distinct were thuds from 20 mm heavy pom-pom guns set on both sides of the road. The shells and bullets passed right above my head.

After some time, the storm of shooting stopped and it became quiet. When the guerrillas noticed that we were moving, their volley started again. Afterward, silence returned. Two hours passed, yet there was no sign of a break through enemy lines. The moon was about to rise. It was now impossible to force through the blockade since we had about 400 elderly, women, children, and patients with us. There was also the danger of the US forces closing in from behind. Besides, we only had limited amounts of ammunition.

Whenever there was the slightest movement on the Japanese side, the enemy showered us with bullets. Eventually, news came that the front line commander Saitô was wounded. Colonel Tozuka and I were shocked, but immediately assigned 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto to replace him. Thus, March 18 passed in this continuous exchange of firepower.

By dusk of March 19, we ordered the front left forces of Noda to attack in the direction of the vast plain to Pavia. But before the command to attack could be made, there was a mighty guerrilla shooting spree that led to the bad news that company commander Noda, Master Sergeant Sô and other main officers of the company were killed in combat. Although Lieutenant Noda had dashed towards enemy positions, his subordinates were terrified by the fierce shooting and did not join him. Noda was shot to death as he was trapped in the enemy’s wire-fence. Master Sergeant Sô got seriously wounded and killed himself with his pistol.

|

Kumai at tochika of the Pavia garrison which was annihilated, in postwar Pavia. Page 101.

|

|

Since the main officers of the company were slain, the Noda force could not make the attack. I felt that a tragic end was rapidly falling upon us and was irritated that no good ideas were forthcoming. I only ordered all the vehicles to be burnt. Mortar fire continued. As I had sent a messenger to see how the Hôjins were doing, I heard that the women and children were getting bored and that some were making tea that the children wanted. They did not comprehend the mortal combat going on so close by, and I was concerned how they would react to this reality.

At around 4 a.m. of March 19, Lieutenant Fujii, commander of the 2nd Company that was posted as rear guard, surprised the headquarters staff by showing up suddenly. He said: ‘Shall the 2nd Company cross the Jaro River on the right and attack from that side? The rear would be empty without their protection, exposing the Hôjin Company, hospital patients, and Hôjin women and children left behind. Otherwise, however, we would all be destroyed.’ Colonel Tozuka then ordered, ‘All right, Fujii. Do that.’ Before long, the Fujii Company crossed the Jaro River. In the hope that other forces would follow them, the headquarters ordered an NCO liaison officer to guide the Hôjin. As soon as the Japanese forces started to cross the river, shouts of the attack – ‘Wah, wah’ – rose at the forefront. With those shouts, the whole group ran along the main road. As it had become light, we waited for the forces that followed within a coconut grove on the left bank of the Jaro River. Eventually, the Kempeitai, the Mizutani Force, the remaining Division forces, the NCO Cadet unit, and the Miyamato Platoon of Noda unit arrived – but without the Hôjin Company, the Hôjin women and children, and the Army Hospital patients.

The Saitô force, which had penetrated through enemy lines, was also out of contact. I dispatched 2nd Lieutenant Itsuki and several soldiers to look for those who were left behind and, if possible, to make contact with the Saitô Force. The headquarters’ group stayed in a dangerous zone three kilometers north of Jaro while waiting for the Hôjin. Soon, 2nd Lieutenant Itsuki returned running out of breath: ‘The enemy tanks are coming. When I was looking for the Hôjin and Army Hospital patients, I met the tanks and came back. At the height of the battle last night, dozens of Japanese and Filipino soldiers had fallen, lying on top of each other.’

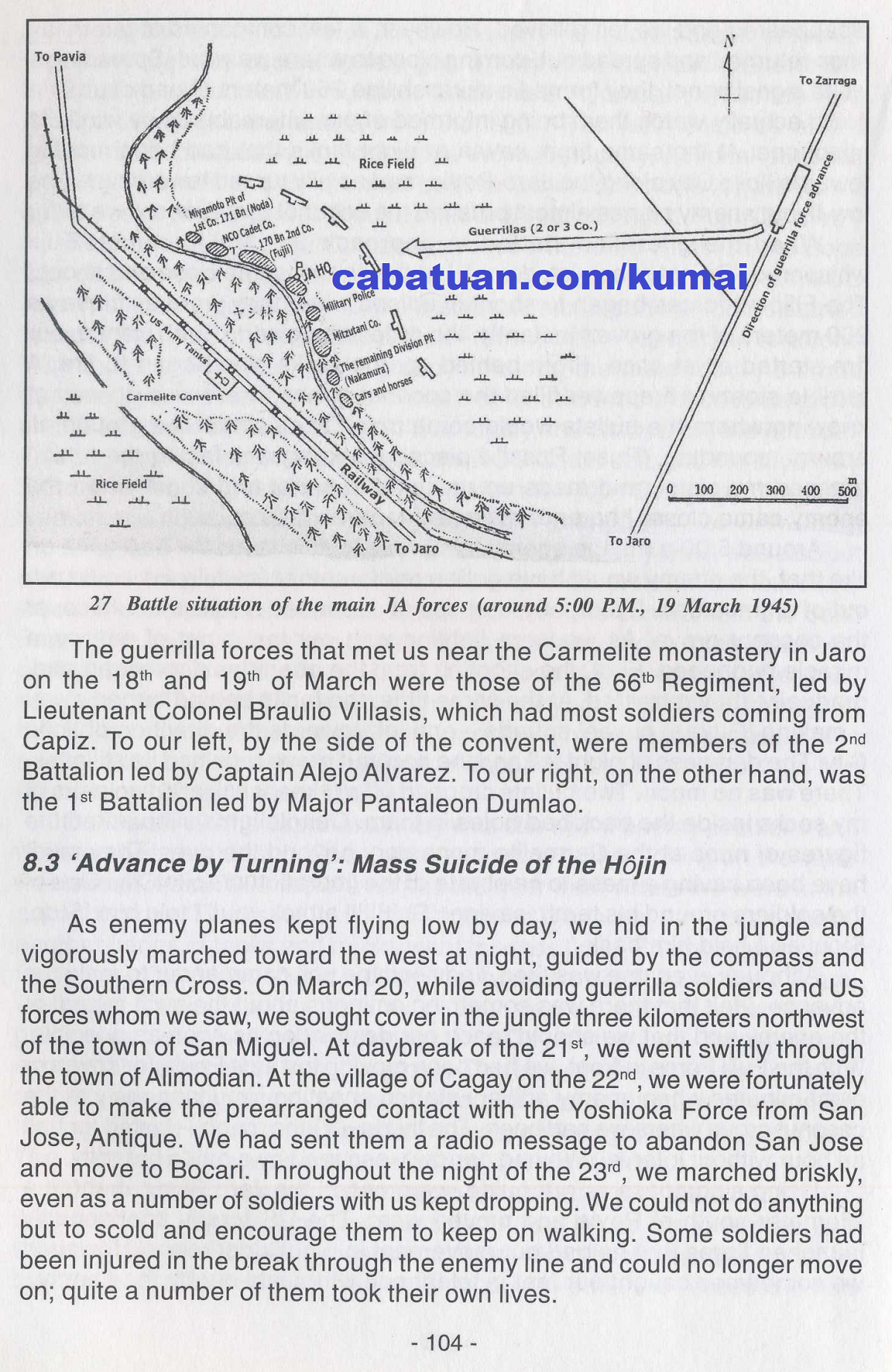

On March 19, the Japanese Army was still within enemy positions and in a worst-case situation. Soon, we saw enemy tanks moving on the Jaro-Pavia road, about 200 meters across the river from where we were in the coconut grove. Trucks full of soldiers followed the tanks. After this column, another series of tanks and trucks went towards Iloilo. Enemy planes were flying low in the skies above looking for Japanese soldiers. In due course, we heard a voice saying, ‘Enemy on this side as well.’ We then saw a great march of guerrillas heading for Iloilo City on the Jaro-Zarraga road, about 800 meters away from the grove. There were several US vehicles but others were on foot, and we could also see a large number of guerrillas moving. On our left were the American forces; on the right were the guerrillas. The Japanese Army was surrounded and could not move.

The march of the enemy that began around 8 a.m. went on late into the afternoon. By this time, local residents had joined the guerrillas and there was no end to their procession. We all hid ourselves in the trenches that the guerrillas had dug. Earlier, around 4 p.m., the procession had disappeared and we felt relieved. However, a few companies of guerrillas soon returned and spread out, coming close to where we were. Spreading a white signal panel, they formed a skirmish line 250 meters ahead of us. We could actually watch them being informed of our whereabouts by wireless telephone. At the same time, seven or eight tanks that had been moving towards Iloilo City along the Jaro-Pavia road noisily turned towards us. The low-flying enemy planes almost brushed the coconut grove where we hid.

When the guerrillas started to approach us, 1st Lieutenant Fujii whispered, ‘Do not shoot yet, do not. Let the enemy come close and shoot.’

The Filipino forces began to shoot in unison when they were as close as 200 meters of the grove. Instantly, the order was given, ‘Fire!’ Hence, our fire started all at once. From behind us, the tanks also began to fire. A terrible storm of firepower filled the coconut grove. There was no way of knowing where the bullets would come from. They struck the ground all around, sounding, ‘Puss! Puss!’ I placed my knapsack facing the tanks, grasped my pistol, and made up my mind to shoot and shoot when the enemy came close. I had not expected to remain so calm.

|

Battle situation of the main JA forces (around 5:00 P.M. 19 March 1945). Page 104.

|

|

Around 5 p.m., the enemy firing rose to its climax. If it had gone on like that, the enemy would have gotten reinforcements while we would run out of ammunition. Eventually, corpses of Japanese soldiers would cover the coconut grove. As we were fighting with our last burst of energy, a miracle happened. First, the shooting from the guerrillas decreased and, gradually, they retreated. At the same time, the tanks behind turned away – making ‘Guyee, guyee’ sounds – and left towards the direction of lloilo City. The darkness of night fell and the coconut grove regained its stillness. There was no moon. Two bullets dropped off my knapsack and two pairs of my socks inside the pack had holes in them. Candlelights silhouetted the figures of nuns at the Carmelite monastery beyond the river. They must have been having a mass to celebrate of the liberation of Iloilo City. One of the soldiers ground his teeth, saying, ‘Shit! I’ll attack you!’ I told him ‘Stop, Stop’ as I held him back.

Although everyone was tired, I advised the unit commander to make an advance. I felt that there was something ominous about the swift retreat of the enemy and that we should reach our destination as soon as possible. With the Fujii Force in front, we had been moving towards Pavia for seven or eight minutes when enemy artillery started shooting simultaneously at the coconut grove where we had been. The thuds – ‘Dahn, dahn’ – lasted for half an hour without interval. We had narrowly escaped by a hair’s breadth.

Using a compass as our guide, we crossed the Jaro River at about a kilometer south of Pavia and moved west. The US forces continuously launched flares that helped our movement in night’s darkness. However, we sometimes caught our feet in telephone wires laid out by the enemy.

The guerrilla forces that met us near the Carmelite monastery in Jaro on the 18th and 19th of March were those of the 66th Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Braulio Villasis, which had most soldiers coming from Capiz. To our left, by the side of the convent, were members of the 2nd Battalion led by Captain Alejo Alvarez. To our right, on the other hand, was the 1st Battalion led by Major Pantaleon Dumlao.

|

|