Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymond G. Stanton looks on.

Cabatuan Airfield

Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan, Iloilo

Panay Island, Philippines, September 2, 1945

|

|

- o -

|

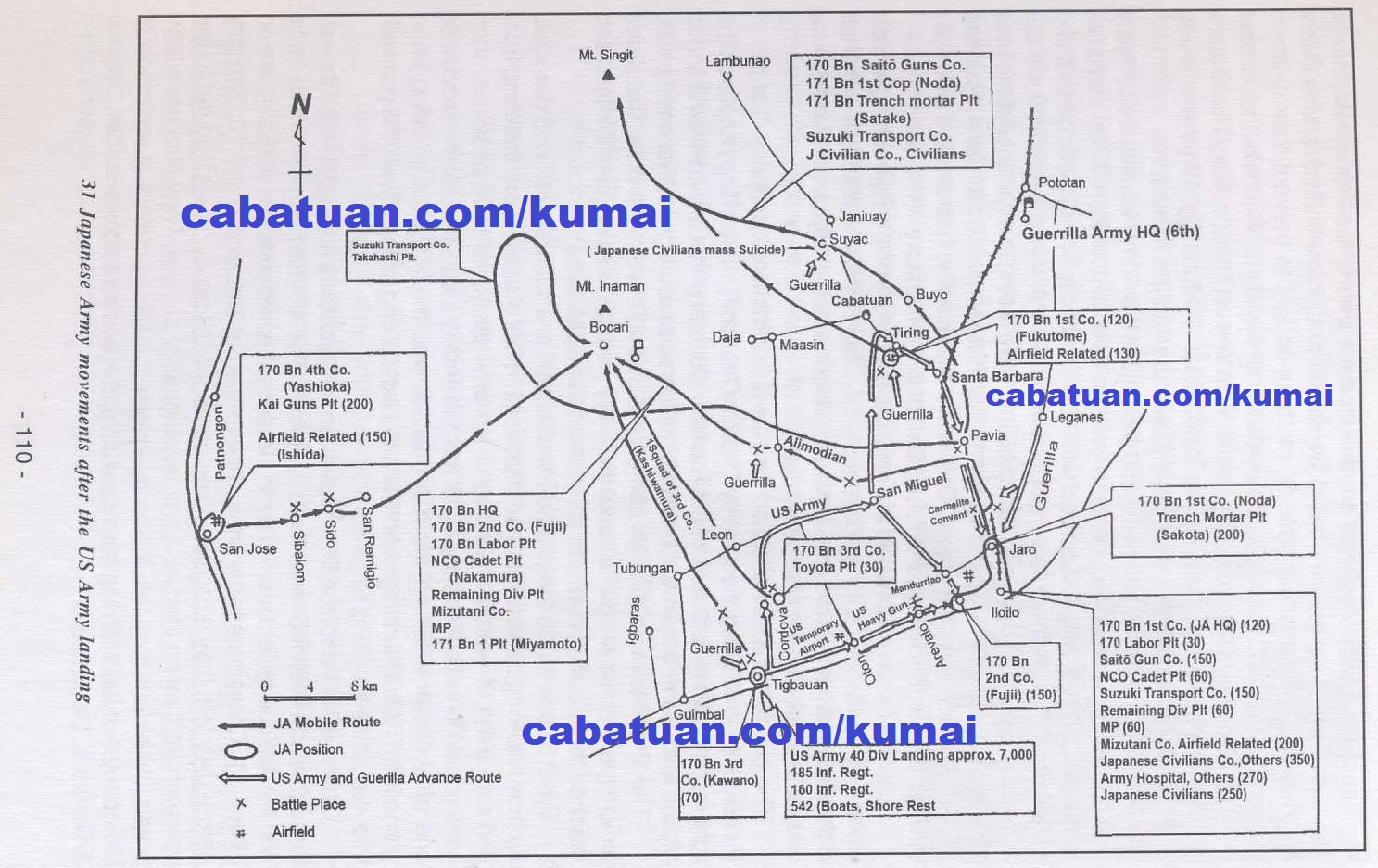

Japanese Army movements after the US Army landing. Page 110.

|

|

Chapter 9 – ISOLATION

9.1 Fighting at Bocari

The village of Bocari is at the foot of the outer rim of a depression around Mt. Inaman that peaked at about 1,350 meters. The outer rim of the basin measured about four kilometers east to west and two to three kilometers from north to south. On both sides of the 10-meter wide river, there were some 600 houses of villagers around terraced and skillfully irrigated rice fields. The people here were raising corn, sweet potato, kamote kahoy (cassava), leek, mongo (mung beans), peanut, and tobacco in areas where water was not easily accessible. In swampy areas, there were taro potatoes; and on the slopes were mangoes and bananas.

Everyday some Japanese soldiers managed to reach Bocari, exhausted, disheveled, and in rags. I met each one of them to hear the circumstances of Japanese soldiers killed in battle that they had spotted along the way. They reported the tragic end of the Army Hospital patients that happened east of Barrio Buyo and the awful scene of around 30 Japaneses soldiers killed naked on a mountain slope north of Leon. I also learned that tanks south of Pavia had killed a number of Japanese soldiers, who had attacked them.

The soldiers who had trailed behind thus came one after the other into Bocari. Nevertheless, the greatest concern was for the forces and the Hôjin under the leadership of Captain Saitô. Those of us in Bocari had been resting, recovering from malnutrition and beri-beri with the abundant food available. That made us more bothered and worried about our separated comrades and the Hôjin.

In early May, 2nd Lieutenant Saeki and his platoon of the Noda Force of the Tanabe unit arrived at headquarters guided by a soldier of the 2nd Company. The Saeki platoon was the messenger/search unit of the Saitô force. Since our separation, it was only then that we learned about the actions of the Saitô unit as well as the mass suicides of the elderly, women and children. Our unit was charged with the care for the Hôjin as the Saitô unit did not have enough food in their position. Escorted by the Suzuki Company, the Hôjin arrived several days later, hobbling in ragged mompe outfits (Japanese trousers). Many had tropical ulcers. They looked miserable like beggars – very different from their days in Iloilo City – and this brought tears to our eyes. Among them was Mr. Kimura, the head of the Japanese Association, who had a beard like that of a goat. So was Miss Ritsuko Kayamori, the only survivor of the Kayamoris, and so on. Each one of them was a pitiful sight.

In the beginning, the area close to Mt. Inaman was the safer area from which food could be obtained and was offered to the Hôjins. Soon, however, there was no more food to consume. Hence, the Hôjin were to be assigned to various units in groups of 14 or 15 members. As we were discussing this distribution of responsibility, a Taiwanese comfort woman named Chiyo came up to me, lamenting, ‘The Hôjin all despise us as Taiwanese and prostitutes. Please, do not divide us but keep us as one group.’ I felt very sorry for them and wondered how I should deal with them. They were the most popular of the groups; most units wanted to be in charge of them. For the sake of the women, and as I wanted to avoid problems that might be caused should they start their prostitution business under the current circumstances, I assigned them to the care of Lieutenant Nakamura of the remaining 10 2nd Division unit who had the reputation of being a strict man.

|

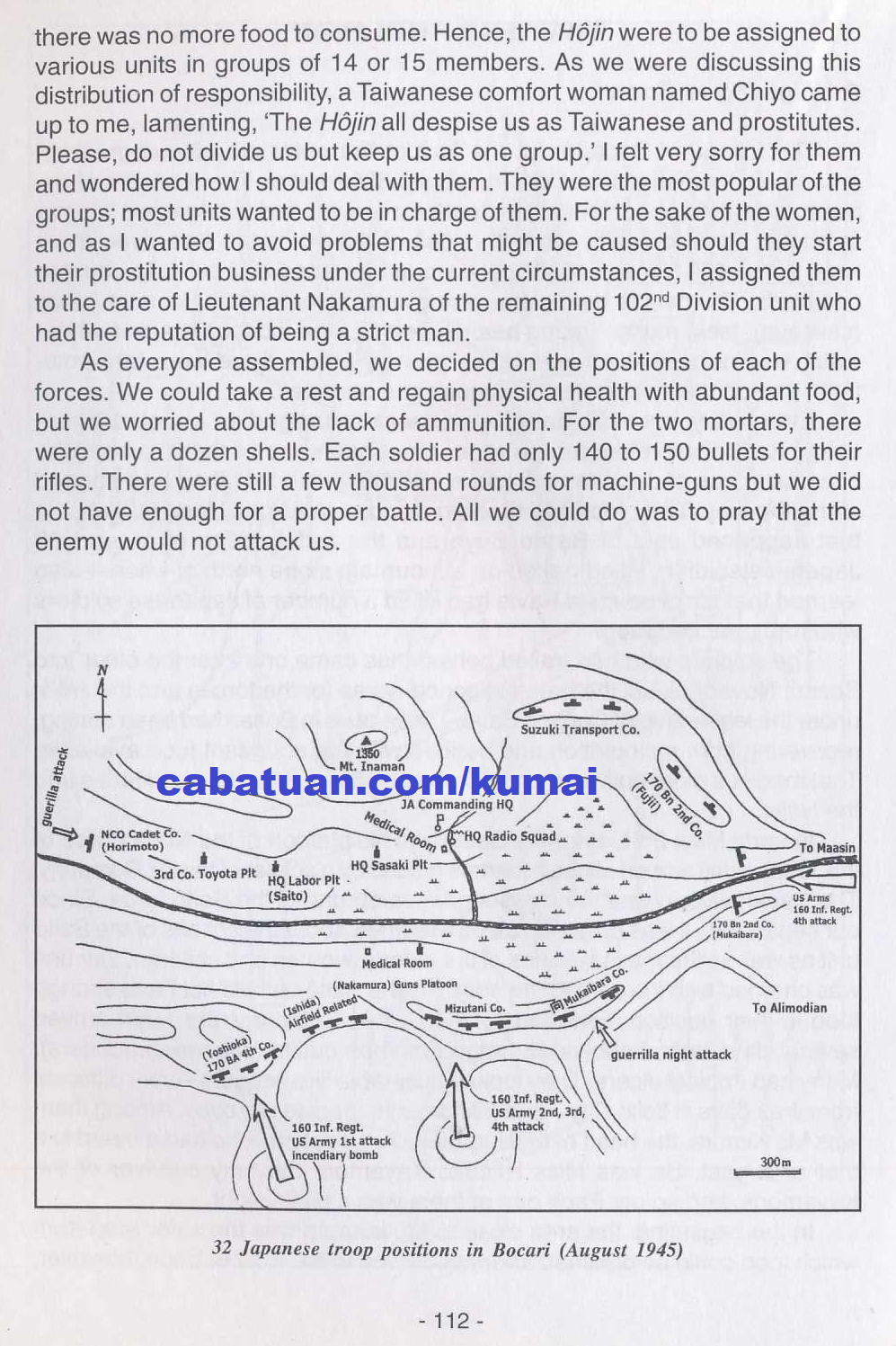

Japanese troop position in Bocari (August 1945). Page 112.

|

|

As everyone assembled, we decided on the positions of each of the forces. We could take a rest and regain physical health with abundant food, but we worried about the lack of ammunition. For the two mortars, there were only a dozen shells. Each soldier had only 140 to 150 bullets for their rifles. There were still a few thousand rounds for machine-guns but we did not have enough for a proper battle. All we could do was to pray that the enemy would not attack us.

When May came, a few companies of US forces started attacking the west position with rifles and light machine-guns. Enemy planes also started strafing. At one time, they even scattered fuel from the air and set it afire, causing the death of several soldiers and leaving the position in flames. The US forces repeatedly attacked the west position of the Yoshioka unit. Because of lack of ammunition they remained patient; they drew the enemy near and shot them. After several assaults that brought about the death of some American soldiers, the attacks on the Yoshioka force ceased.

One thing about the US fighting style that made us feel relaxed was that they never attacked at night. Therefore, we could sleep without concern. Since we were taking it too easy, a dozen guerrillas broke in one night through a gap between the front positions and attacked the nipa houses of the Mukaibara force. Luckily, they quickly fought back and the enemy retreated. Thus, the guerrillas who made occasional sudden raids were more frightening for us than the Americans.

The US forces continued to attack a few companies and to conduct air raids. Nonetheless, we did not have much difficulty. To obtain information on the enemy, we were listening to the Japanese radio broadcasts from Saigon and the American broadcasts in Japanese from San Francisco. They reported that the US forces that landed in Okinawa on April 1 were pressing in on the Japanese Army. After the capture of Okinawa, the attack by the Allied forces on Japan proper would not be far away.

Towards the end of June, a large group of American soldiers – numbering more than a battalion–suddenly appeared on the plateau, about 500 meters in front of the Mizutani force. From morning until night, they fired hundreds of mortar shells. Seen from the headquarters sited on the slope of Mt. Inaman, clouds of mud covered the position of the Mizutani force. All the sheltering foliage burnt to the ground and left the position unprotected. For a few days more, the US forces patiently kept on shelling. We were envious of the large quantities of ammunition that they wasted.

The US attack intensified when the position was exposed. At first, the barrage of mortar fire was preventing the soldiers of the Mizutani force from emerging from their trenches. Then, the American soldiers started climbing up the slope towards them. Because we were running out of ammunition, the Mizutani force did not retaliate even with a single bullet. The US soldiers came as close as a hundred meters from their position when, following the signal to ‘Fire!’, the Japanese soldiers began firing all at once. They were just sporadically firing their rifles, but the US soldiers ran back for their lives. Thus, the attack ended for the day.

The next morning, the Americans once again started shelling with mortars. This time, however, the shells had fuses that went off instantly. They largely left the trenches undamaged, producing holes on the ground only about 40 to 50 centimeters deep. The Mizutani force hid lying flat in the trenches during the shelling and observed this style of the enemy attack. When the firing ended, they ran up to their positions and waited for the Americans to approach. Soon, around two companies of US soldiers started to climb up the slope shooting their light machine-guns and carbines. We could distinguish each of their faces. They also looked tired from the tropical heat and steep mountains but continued to climb with determination. When they neared about a hundred meters, the Mizutani force started firing. The Americans retreated, stumbling down the hill, thus ending the morning attack. As expected, after lunch, the US forces started again and repeated the process.

|

A view of the hills of the Japanese hold-out at Bocari. Page 113.

|

|

Eventually, we saw a crowd of American soldiers on the plateau about 500 meters ahead. Through binoculars, we could see them looking at us in a relaxed mood – smoking, chewing gum.

We had withheld the use of heavy machine guns and mortars. However, since there was abundant game before us, it was silly not to take action. What is more, it was not good for our morale. Upon discussion, Colonel Tozuka, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I decided to try shooting into the enemy with heavy machine guns and mortars.

Early the next morning, we set as many heavy machine guns as we had – which were just four or five – in the positions of the Yoshioka, Mukaibara, and Mizutani forces that aimed at the plateau from three directions. The Japanese soldiers awaited the arrival of the enemy with anticipation. Suddenly, the US soldiers showed up and swelled into a crowd, smoking and walking around. With the order, ‘Fire!’ several shells exploded on the slope behind the plateau. At the same time machine guns from three directions were fired simultaneously – ‘Dah-da-da-da-da!’ Instantly, the US soldiers scattered like spiders. Some of them fell down on our side of the slope and fled. Cries of joy resounded from our positions. However, the incident was short-lived. The American soldiers retreated quickly and disappeared in a flash.

From the excellent retreat of the US soldiers, it was obvious they were experienced veterans of battles. Now that we had shown them all we had, we worried about their reaction. However, it was clear that the encounter also caused them some casualties. Their retreat stopped the attack for the day and they did not appear on the plateau on the next day.

By that time, each of the Japanese forces was lacking in salt and meat. We ditched foraging parties to steal food from the houses abandoned by the villagers. The imperial army had become thieves and bandits.

In order to cultivate rice, I organized an agricultural work group to plant rice and cuttings of kamote-kahoy root using the primitive tools the local residents had left behind.

|

|